Developing a ‘Lancashire Sensibility’: thoughts for Lancashire Day, 2022

Paul Salveson

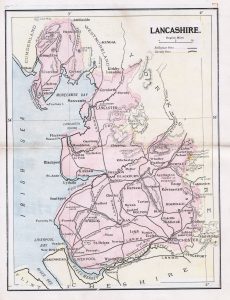

Over the last year I’ve been working on a book about Lancashire history, identity and culture. Lancastrians – Mills, Mines and Minarets will appear next summer. A central part of its argument is that we need to revive a ‘Lancashire Sensibility’ which is forward-looking and inclusive – and takes in the whole of ‘historic Lancashire’. To do that, we need to go back before we can go forward and look at how a ‘Lancashire Sensibility’ emerged in the past.

It was a central part of a regional identity that took in speech, dress, manners, diet – pretty much every aspect of how we lived. In 1951 the (Labour) Minister of Education, George Tomlinson, wrote the foreword to the journal of the newly-established Lancashire Dialect Society:

“I have a feeling that we cannot afford to lose the characteristic features of our County, which are bound up in no small degree with the accents of its people and our own particular dialect… for since I became a Minister of the Crown, in every part of the country people have come to me at the end of a meeting, shaken me by the hand and said, ‘I too come from Lancashire,’ and it was grand to hear the accent again.”

The ‘Lancashire sensibility’ was very much a part of the social and intellectual make-up of most sections of society by the middle of the nineteenth century. It included much of the aspiring middle class, sections of the aristocracy and some ‘respectable’ working men. Women were part of it; the leader of the women’s suffrage movement Emmeline Pankhurst was always fond of stressing her ‘Lancashire’ roots.

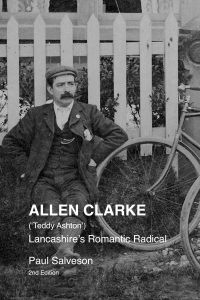

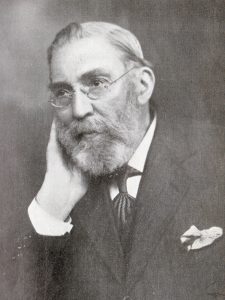

It linked with the idea of a ‘Lancashire Patriotism’ which emerged in the 1880s. Speaking in the middle of the First World War, Rossendale Liberal politician and historian Samuel Compston said that “if patriotism is a virtue, especially in these days, surely county clanship, in no narrow sense, is a virtue also.”  The socialist writer Allen Clarke was one of the foremost proponents of a Lancashire sensibility, through his stories, poems and songs. Many Conservative figures such as the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres were proud of their Lancashire roots and supported bodies which promoted Lancashire culture.

The socialist writer Allen Clarke was one of the foremost proponents of a Lancashire sensibility, through his stories, poems and songs. Many Conservative figures such as the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres were proud of their Lancashire roots and supported bodies which promoted Lancashire culture.

Lancashire speech – from ‘accent’ to full-blown dialect, or ‘broad Lancashire’, formed an important part of Lancashire identity and sensibility. Debates over its use, among Lancastrians over the last hundreds years and more, highlight some of the wider issues around Lancashire identity. During the late 1920s and early 1930s there was an on-going debate about whether dialect speech should be encouraged, or allowed to die. The Bury dialect writer T. Thompson, who had a regular column in that sadly departed champion of all things Lancashire, The Manchester Guardian, spoke in defence of dialect speech at a meeting of the Manchester Literary Club in 1938. He argued against attempts to ‘standardise’ English and stressed that “language is a living thing, always changing, and if they standardised it, it became a

dead thing.” Allen Clarke commented on Lancastrians’ ability to ‘switch’ from standard English to dialect, as the occasion required it: “Just as in Wales, they talk both Welsh and English, what’s wrong about Lancashire using its dialect as well the English language? As it is not so much the tool as the man who uses it…so it is not the mere words but the thoughts and sentiments that make the power and beauty of a language. While the Lancashire dialect is equal to any other language in pathos, is fundamental characteristic is its humour, mostly cheery and kindly, and in that respect it is first and foremost in the world.”

An essential part of the creation of a ‘Lancashire sensibility’ was the emergence of a distinctive ‘intelligentsia’ which provided a network of influential figures. The Manchester Literary Club was central to this. It was founded in 1862 and its aims were to “encourage the pursuit of literature and art; to promote research in the several departments of intellectual work and to protect the interests of authors in Lancashire; to publish from time to time works illustrating or elucidating the literature and history of the county…”

A typical member was Samuel Barlow, a partner in a bleach works at Stakehill near Middleton. As well as being an active member of the Manchester Literary Club he was a founder of the city’s Arts Club, an artist and botanist and had a strong interest in Lancashire dialect. William E.A. Axon was another prominent member with wide interests. He became a central figure in Manchester – and Lancashire – intellectual circles towards the end of the nineteenth century. In 1874 he joined the staff of The Manchester Guardian as its librarian. He had already been writing for the Guardian, and used his pen in support of the anti-slavery cause during the American Civil War.

Lancashire developed a number of cultural associations which provided a network for the county’s intellectual communities. The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire was founded in Liverpool in 1848. The Lancashire Authors’ Association (for ‘writers and lovers of Lancashire literature’) was established in 1909 on the initiative of Allen Clarke. Its Library was created in 1921 from members’ donations and is now the largest collection of regional literature in the UK. It is housed as a special collection in the University of Bolton Library.

The Manchester Section of the Society of Chemical Industry seems an unlikely body to take a broad view of culture in Lancashire. However, in 1928 the Society was instrumental in commissioning The Soul of

Manchester, to mark the Society’s Manchester meeting the following year. The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres (also vice-president of the Lancashire Authors’ Association) contributed the introductory essay on ‘The Soul of Cities’ in which Manchester is clearly positioned as the county ‘capital’ but very much a part of Lancashire.

The Co-operative Movement came closest to providing an intellectual framework for working class men and women in the years between the 1850s and 1960s. It was a network of local, independent, societies. The larger ones had substantial libraries, reading rooms and lecture theatres, with frequent lectures by eminent speakers, often on aspects of Lancashire history and culture.

The post-war years saw the coming of mass entertainment, particularly television – which was less suited to a more regional culture. Was it, finally, the beginning of the end that had been forecast for so long?

Actually, no. Go to schools in many parts of Oldham, Rochdale or Bolton and you will hear young Asian as well as white English children speaking ‘broad Lanky’. After its demise being forecast for many decades, it refuses to die, and with it that broader sense of ‘being Lancashire’.

We need a revived Lancashire sensibility that is about more than just dialect and speech, embracing culture in a general sense. We already have Friends of Real Lancashire and the Lancashire Society flying the

red rose. We need to up our game and tap into people’s continuing sense of identity which is at risk of being subsumed into the amorphous city-regions. A campaign to re-unite and re-imagine Lancashire needs a higher profile and cross-party support.

A reformed Lancashire within its historic boundaries makes sense as a regional economic unit but also chimes with people’s identities – in a way that artificial ‘city regions’ never will. An alternative is the idea of the ‘county region’ which forms an organic whole without one centre becoming over-dominant. People in Bolton, Oldham, Rochdale and other towns don’t want to become mere commuter suburbs of Manchester. Nearly 50 years on from the creation of ‘Greater Manchester’ the so-called ‘city region’ still has little legitimacy. If there was a referendum tomorrow on being part of Lancashire or ‘Greater Manchester’ I have little doubt about the result. There is an alternative – a greater ‘Lancastria’ that celebrates all of our county, not just the main cities. A starting point must be the re-creation of a new ‘Lancashire Sensibility’ which was so much a part of life in the 19th and early 20th century but celebrates a modern county identity. That’s why we should celebrate our Lancashire Day – and make it something that everyone living and working in Lancashire can celebrate.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Lancastrians: Mills, Mines and Minarets will be published by Hurst in June 2023. See www.hurstpublishers.com

This article is was first published in The Lancastrian, the magazine of Friends of Real Lancashire in September 2022. See www.forl.org.uk

My biography of Allen Clarke (‘Lancashire’s Romantic Radical’) is available at a special price of £10 including postage. Email me on paul.salveson@myphone.coop for details

2 replies on “Thoughts for Lancashire Day 2022: Towards a new Lancashire Sensibility”

Yes indeed, great edition on real Lancashire. I still cherish my accent made Leigh and applied in Rochdale. Looking forward to the book. Regards Brian Leather

Excellent post and I look forward to reading the book. Any chance of including something on the Portico Library, Moseley St, Manchester. Can help with that if you are interested.