Lancashire Loominary No. 5

July 2021

It’s summer…time for a new book to blossom

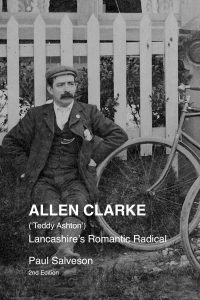

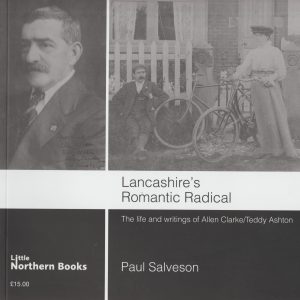

The new and updated edition of my biography of Allen Clarke (Allen Clarke – Teddy Ashton: Lancashire’s Romantic Radical) is back from the printers and looks good, apart from a few annoying typos. There is a lot of new material in it, including an entirely new chapter on Clarke’s  railway writings. The Bolton News carried a feature on his novels recently (June 16th) – there’s a word version of it below. The official publication date will be September 1st but I am doing a pre-publication offer for £15, with free local delivery in the Bolton area, or add on £3 for UK postage. You can download an order form from my website, below, or there’s one at the back of this newsletetr: http://lancashireloominary.co.uk/index.html/order-form

railway writings. The Bolton News carried a feature on his novels recently (June 16th) – there’s a word version of it below. The official publication date will be September 1st but I am doing a pre-publication offer for £15, with free local delivery in the Bolton area, or add on £3 for UK postage. You can download an order form from my website, below, or there’s one at the back of this newsletetr: http://lancashireloominary.co.uk/index.html/order-form

I’m hoping to do a number of launch events in late August or early September. If you’d like to host a launch, even for a small group of people, please let me know.

Who was Allen Clarke?

More than any other writer of the early 20th century, he captured the essence of life in the industrial North. He was born into a working class Bolton family in 1863 but most of his later life was spent in Blackpool. He followed his parents into the mill, starting as a ‘half-timer at the age of 11. He went on to write over 20 novels, dozens of short stories and poems as well as factual accounts of life in the factories, one of which was translated into Russian by Tolstoy, whom he greatly admired as a writer and political thinker.

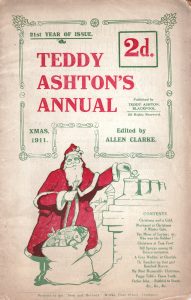

His sketches in Lancashire dialect (written as ‘Teddy Ashton’) “poked sly fun and undermining sarcasm” at the social evils of the day and sold over a million copies. His newspapers, like Teddy Ashton’s Northern

Weekly, were read and passed round mill and factory by thousands. His book Windmill Land popularised the Fylde countryside and is a mix of history, folklore and roadsides chats.

The new edition includes lots of new material which sheds more light on this important, but neglected figure in English literature who was loved by thousands of his readers in the textile districts of Lancashire and Yorkshire. He had a close relationship with his audience and one group of Manchester railwaymen wrote to Clarke protesting at the abrupt way he ended one of his novels!

As well as his own work, Clarke encouraged other working class men and women to write for his newspapers and was instrumental in forming the Lancashire Authors’ Association in 1911. His ‘readers’ picnics’ attracted hundreds of visitors, often arriving by train or bicycle.

One, at Barrow Bridge near Bolton in 1901, was held to raise funds for the locked-out quarry workers at Penrhyn, Wales; it was attended by several thousand, including the Clarion Choir. He mobilised his child readers to raise funds for the starving families and organised cycle trips to the quarry villages.

After his move to Blackpool he created the Blackpool Ramble Club, one of the biggest walking clubs in the country. He died in December 1935 and is buried at Marton Cemetery, close to the windmill that is now a shrine to his memory.

Unlikely Pioneers

I’ve been working on a new edition of my ‘Whitman’ book – With Walt Whitman in Bolton – spirituality, sex and socialism in a Northern Mill town –  last published in 2019 though little changed since 2009. I’ve combined it with a lengthy paper on Whitman’s influence on ‘Northern Socialism’ and re-titled it Unlikely Pioneers: Walt Whitman, the Bolton Boys and Northern Socialism.

last published in 2019 though little changed since 2009. I’ve combined it with a lengthy paper on Whitman’s influence on ‘Northern Socialism’ and re-titled it Unlikely Pioneers: Walt Whitman, the Bolton Boys and Northern Socialism.

I’m debating whether to do a print edition or just publish it on kindle, which makes life easier in terms of an international readership. Readers’ views welcome!

The latest Salvo

The latest edition of my blog/e-newsletter or whatever, is out and can be downloaded from here:

http://lancashireloominary.co.uk/index.html/northern-weekly-salvo-294

The latest edition carries comment on the Labour Party’s current quandaries, progressive regionalism and the latest Government ‘Plan for Rail’. There’s a Salvo take on the recent Lib Dem by-election victory and comments on Batley and Spen, which is now history. The media had more or less conceded victory to the Tories; my take was that they could be wrong, and they were.

The ‘Bolton novels’ of Allen Clarke

Allen Clarke, born in Daubhill (Bolton) in 1863, was one of the most important figures in Northern literature between the early 1890s and late 1930s. Today his work is largely forgotten. Yet he was loved by tens of thousands of Lancashire mill workers and had an astonishing output of dialect sketches, poetry, journalism and works of philosophy. He wrote over 20 novels, most of which were never published in book form, but appeared in newspapers across Britain and even beyond.

Most of his novels are set in Bolton, where he was born and bred. He was never part of the upper class literati – his parents were mill workers, and he started his working life as a half-timer at the age of 11.

His subject matter was the people he knew and the places he grew up in. His parents encouraged his love of writing; at the age of 14 he won a national prize for one of his poems. As his writing developed he had a clear aim – to be a writer of the people and for the people. In 1896 he said: “My aim today is to give the working class life (of Lancashire principally, for that I know best) faithful expression in the literature of England.”

His first published novel was The Lass at the Man and Scythe, written in 1889 and published in book form (by himself) in 1891. It was printed by Pendlebury’s of Bolton. The ‘Lass’ was later revised and extended, re- titled John O’God’s Sending. It is a story of the Civil War, set in Bolton in 1644. It contained many of the themes that featured in his later novels. There is tragedy, a conventional love story, and a healthy dose of radical politics. His preface to the first edition of the book is an early example of his attempt to engage the reader:

“With the aid of that wizard’s wand, a pen, dipped into that magic fluid, ink, the Boltonians who live and move again (at least I hope so) in the following pages have been temporarily raised from the dead. For taking the liberty of resurrecting them somewhat prematurely I beg their pardon. If I have done the business clumsily and inconvenienced these characters in any manner whatever I humbly tender my apologies. I am but a novice at the work……”

The novel revolves around the ancient Bolton pub, The Man and Scythe, still standing opposite the town cross, where the Earl of Derby was executed for his part in the Siege of Bolton in 1644. Royalist soldiers, led by the Earl and Prince Rupert, besieged the town siege and massacred a large number of the townspeople, who supported the Parliamentary side. Clarke sets the wider political context in characteristic style:

“The war that was taking up the time, money, and blood of the nation at this period was a struggle for supremacy between King and Parliament. The King wanted to do exactly as he pleased; the people, as represented by Parliament – wanted to do what they pleased. As a rule, when two parties each resolve to please themselves, it pleases neither. It was so in this instance. Both were obstinate. The monarch had on his side ‘the divine right of Kings’; but that is not much when opposed to the superior force of revolutionary masses.”

Clarke favoured the Parliamentary side but the novel shows that things are never black and white, and creates some positive, human characters amongst the Royalists.

A very important part of this first novel is the extensive use of dialect amongst its characters. Early in the novel we find this exchange between Bolton characters, sat in the pub debating the war:

“How think ye the cavaliers will fare in York?” asked Isaiah Crompton.

“They sen they’ll howd eawt till th’King sends a force to their relief,” said Cockerel, “though for my part I think as they’ll have hard wark for’t keep Fairfax eawt o’th’city.”

“Wheer’s that wild Prince Rupert, what feights like Satan?” queried Roger Roscoe, a farmer.

“Deawn tort Lunnon, somewhere, i’them forrin parts,” replied another.

The novel was a success. Readers enjoyed the local connections, the ‘homely’ characterisation and use of dialect, the love interest combined with the horror and violence of the siege. It was subsequently re-written and enlarged as John O’God’s Sending and published in book form in 1919.

His next novel was The Knobstick, completed in 1891 and serialised in his paper The Bolton Trotter from October 21st 1892 and later published in book form. ‘Knobstick’ is an abusive Lancashire term for strike-breaker or ‘blackleg’ which has long gone out of use. This time Clarke used a near-contemporary event – the Bolton Engineers’ Strike of 1887 – as the backdrop to the story.

Some of Clarke’s themes from The Lass at the Man and Scythe re-emerge: a love story, a dramatic event – in this case the strike, with a powerful riot scene. The novel was celebrated by the East German writer Mary Ashraf in a schoalrly article in 1976, who identifies the beginning of the novel as being of very high literary quality, suggesting “if that quality had been maintained throughout, the book might have been a masterpiece.”

The engineers’ strike is a central part of the novel and Clarke builds up a sense of an impending struggle through the union secretary Peter Banks and his wife:

“We’re gooin to strike Jane,” said Peter Banks to his wife one evening, speaking, as he always did to her, in the dialect.

“God forbid!” she exclaimed.

“Well, it’s so for aw that,” continued Peter, “an I’m afraid as it’ll come off this time. Th’men’s gradely dissatisfied, an fully resolved to have mooar money…It’ll be a mighty struggle if it begins and there’s dozen’s what’ll ne’er see o’er it. Of course eaur society’s very rich at present an’ con howd eaut a good while; but t’mesturs con howd eaut longer. I’m willin for t’ strike anyday, but I’d rayther not. I con feight as weel as anybody when I’m put to, but it seems a silly gam to me.”

It’s melodramatic stuff but well told; it appealed to the readers he was aiming at. After tragedy there is a happy ending with hero and heroine married; the strike ends and a new era begins in the town, with working men elected to the council.

During the 1890s Clarke was working flat out, editing and publishing his Northern Weekly. He wrote much of the copy, including a steady stream of novels including The Little Weaver, Lancashire Lasses and Lads, A Daughter of the Factory, A Curate of Christ’s, For a Man’s Sake and Slaves of Shuttle and Spindle. All of these are set in the Lancashire mill towns, mostly Bolton – often fictionalised as ‘Spindleton’.

The Little Weaver proved popular with his readers, who identified with the characters in the tale; as so with most of his novels, it was about people like them. It has this powerful image of a mill coming to life on Monday morning:

“Then, slowly, at six o’clock precisely, there stole a huzzing murmur on the silence; the shafts began to revolve, the straps that chained the looms creaked, stretched and yawned, as if reluctant to begin their duty, and commenced to climb languidly up to the ceiling, quickening their speed with every turn; the huzzing murmur grew and grew; the weavers touched the levers of their looms one by one, and set them on. The murmur had now become a rattling roar; the sound swelled; the straps whizzed faster; the threads of the warp flowed into the loom like a slow broad stream, and the shuttle darted across them like a swallow, binding them together and making them into cloth; there was creaking and groaning of wheels; the hissing and spluttering of leather straps, as if the animal moaned painfully in its hide; the air grew warmer; the noise became deafening; you could not hear your own voice; and the weaving shed was in full swing.”

Clarke hated what industrialism had done to the Lancashire countryside. In Driving – a tale of weavers and their work, he contrasts what Lancashire once was with how it is day, but even here there is a sense of a tremendous human achievement which has somehow been abused:

“What a marvellous transformation James Watt’s steam engine, aided by the spinning and weaving inventions of Kay, Hargreaves and Crompton had wrought in a hundred years; an agricultural and pasturing shire had been turned into a county of manufacture; Lancashire’s wild moorland vales had become the smoky workshop of the world; and once sweet hillsides were now cinder-heaps and once- bright brooks were now sinking sewers.”

Lancashire Lasses and Lads, set in Bolton and Farnworth, was first published 1896 and in book form 10 years later. The hero, Dick Dickinson, is the son of a factory master who forces his son to leave the family home and ‘descend’ into the working class, where he meets and falls in love with a young weaver, Hannah. Again, Clarke is fascinated by the awesome power and beauty of the factory contrasted with the reality of life inside the mills. Dick Dickinson, when he arrives in Bolton early in the morning, sees the mills coming to life:

“Lights began to show in the great factories of four or five stories, with their many windows. Soon they were all lit up like a vast illumination. ‘Very pretty to look at from the outside, and at a distance on a black frosty morning,’ said Dick, ‘but it’s a different matter toiling inside them’.”

Clarke was a friend of the Tillotson family which published The Bolton Evening News and Bolton Journal, both of which carried his writing, long after he had left Bolton to live in Blackpool. The company set up the Tillotson Newspaper Fiction Bureau to syndicate novels and short stories for newspapers across the British Empire. Many of Clarke’s novels and short stories were published in such seemingly unlikely newspapers as The Forfar Herald, Western Evening Herald, The Devon Valley Tribune (Clackmannanshire) and The Kilrush Herald and the Kilkee Gazette of West Clare. Quite what they made of the Lancashire dialect I can’t imagine.

Clarke’s novels were of their time but remain readable and offer real insight into Lancashire life in the late 19th century. Some of them deserve re-printing, perhaps starting with ‘The Knobstick’.

It’s ‘Wakes Week’….or is it ‘Bolton Holidays’?

Across Lancashire, from late June, the cotton towns started to close down for the fortnightly holiday. It was actually a short-lived tradition, taking off after the Second World War (when paid holidays came in) and ending with the decline of the cotton industry in the 1980s. Some places called it ‘Wakes Week’ though my own memories in Bolton (and many friends) are of ‘Bolton Holidays’. Take your pick – maybe there were localised differences, with Great Lever people calling it ‘Bowtun Holidays’ and Daubhill people saying ‘Wakes Week’? Over the Pennines in Yorkshire, Huddersfield had separate holidays for engineers and textile workers, which was a bit tricky if dad worked in engineering and mum in the mill, as many people did. Further research is needed. Anyroad, take a look at this, from last week’s Bolton News:

https://www.theboltonnews.co.uk/news/19416154.wakes-week—folk-bolton-headed-off-coast/

Make Greater Manchester Greater (from Salvo 294)

As a proud Boltonian I have never been comfortable with the idea of being part of ‘Greater Manchster’ preferring the original, admittedly cumbersome title of ‘South East Lancashire and North-East Cheshire’ used by the buses. SELNEC. They could have added ‘with bits of The West Riding of the Yorkshire’ recognising Saddleworth’s inclusion in the area. Greater Manchester doesn’t really work. And I deeply disagree

with the contemporary obsession with ‘city regions’ in which the ‘city’ will always dominate the satellite towns. Years ago I remember my friend David Begg talking about ‘Greater Manchester’ in a transport context pointing out that its hinterland goes well beyond its current boundaries. He was right then (1990s?) and that perception is truer today than ever. Blackburn and North-East Lancashire are very much part of the wider hinterland that relates to Manchester itself. So is Preston and – more arguably – Warrington. Lancashire itself, in administrative terms, is a total shambles, with unitary authorities for Blackpool and ‘Blackburn with Darwen’ and talk of carving up what remains of local government into larger and even less accountable districts.

There is an alternative! Make Greater Manchester into a much bigger entity, more or less recreating ‘Lancashire’ but with boundaries which make political, economic and cultural sense now. I’d be inclined to leave Merseyside (or ‘Liverpool City Region’) as a separate entity with Chester. But it would all need a lot of debate and discussion rather than the forced imposition of an alien concept, back in 1974. The new ‘Greater Lancastria’ should have an elected assembly along similar lines to the existing devolved administrations, with re-constituted local authorities which should have more, rather than less, power.

Other books from th’same shed: Moorlands, Memories and Reflections

Still available. 2020 was the centenary of the publication of Allen Clarke’s Moorlands and Memories, sub-titled ‘rambles and rides in the fair places of Steam-Engine Land’. It’s a lovely book, very readable and entertaining, even if he sometimes got his historical facts slightly wrong. It was set in the area which is now described as ‘The West Pennine Moors’ It also included some fascinating accounts of life in Bolton itself in the years between 1870 and the First World War, with accounts of the great engineers’ strike of 1887, the growth of the co-operative movement and the many characters whom Clarke knew as a boy or young man.

My book is a centenary tribute to Clarke’s classic – Moorlands, Memories  and Reflections. It isn’t a ‘then and now’ sort of thing though I do make some historical comparisons, and speculate what Clarke would have thought of certain aspects of his beloved Lancashire today. There are 28 chapters, covering locations and subjects which Clarke wrote about in the original book, with a few additions. It includes the Winter Hill rights-of-way battle of 1896 and Darwen’s ‘freeing of the moors’; a few additional snippets about the Bolton ‘Whitmanites’, handloom-weaving, railway reminiscences, the remarkable story of ‘The Larks of Dean’ and Lancashire’s honourable tradition of supporting refugees (including the much-loved Pedro of Halliwell Road). The story of Lancashire children’s practical support for the locked-out quarryworkers of Snowdonia in 1900-3 is covered in some detail, including the remarkable ‘Teddy Ashton Picnic’ of 1901 in Barrow Bridge, which attracted 10,000 people. It will be profusely illustrated.

and Reflections. It isn’t a ‘then and now’ sort of thing though I do make some historical comparisons, and speculate what Clarke would have thought of certain aspects of his beloved Lancashire today. There are 28 chapters, covering locations and subjects which Clarke wrote about in the original book, with a few additions. It includes the Winter Hill rights-of-way battle of 1896 and Darwen’s ‘freeing of the moors’; a few additional snippets about the Bolton ‘Whitmanites’, handloom-weaving, railway reminiscences, the remarkable story of ‘The Larks of Dean’ and Lancashire’s honourable tradition of supporting refugees (including the much-loved Pedro of Halliwell Road). The story of Lancashire children’s practical support for the locked-out quarryworkers of Snowdonia in 1900-3 is covered in some detail, including the remarkable ‘Teddy Ashton Picnic’ of 1901 in Barrow Bridge, which attracted 10,000 people. It will be profusely illustrated.

It is available price £21, with £4 post and packing. Go to http://lancashireloominary.co.uk/index.html/order-form

for details of how to order. I can do free delivery locally (within 6 miles of Bolton).

The Works: a tale of love, lust, labour and locomotives

I’ve had a steady flow of orders for The Works, my novel set mostly in Horwich Loco Works in the 1970s and 1980s, but bringing the tale up to date and beyond – a fictional story of a workers’ occupation, Labour politics, a ‘people’s franchise’ and Chinese investment in UK rail. I’ve had lots of good reactions to it, with some people reading it in one  session. The Morning Star hated it. If you want a copy I can offer it for £10 plus £2.50 postage to those of you on this mailing list. Please make cheques payable to ‘Paul Salveson’ and post to my Bolton address above or send the money by bank transfer (a/c Dr PS Salveson 23448954 sort code 53-61-07 and email me with your address). If you are local I can do free delivery by e-bike (so just a tenner). There is a kindle version available price £4.99 and you can also buy it off Amazon. See www.lancashireloominary.co.uk

session. The Morning Star hated it. If you want a copy I can offer it for £10 plus £2.50 postage to those of you on this mailing list. Please make cheques payable to ‘Paul Salveson’ and post to my Bolton address above or send the money by bank transfer (a/c Dr PS Salveson 23448954 sort code 53-61-07 and email me with your address). If you are local I can do free delivery by e-bike (so just a tenner). There is a kindle version available price £4.99 and you can also buy it off Amazon. See www.lancashireloominary.co.uk

If you’ve already read and hopefully enjoyed The Works it would be great if you could do a short review of it on my facebook page (Lancashire Loominary). Feedback on how it could have been better is also welcome, especially as I’m starting work on the next novel (see below).

The Works is available in the following outlets – please support them! If you know of any local shop which might like to take my books please let me know. I do a third discount, sale or return.

- Justicia Fair Trade Shop, Knowsley Street, Bolton

- The Wright Reads, Winter Hey Lane, Horwich (currently closed)

- Bunbury’s Real Ale Shop, 397 Chorley Old Road

- Pendle Heritage Centre, Barrowfoed

- Smethurst’s Newsagents, Markland Hill

- Pike Snack Shack, Rivington

- Horwich Heritage Centre

- A Small Good Thing, Church Road Bolton

- Carnforth Bookshop

- The Lakeland Gallery, Bo’ness

- Penrallt Bookshop, Machynlleth

Points and Crossings in Chartist……

I write a regular column called ‘Points and Crossings’ for Chartist magazine, one of the brightest and most intelligent magazines of the left. A recent column was a critique of Labour’s nationalisation plans for the railways: https://www.chartist.org.uk/labours-british-railways-mark-2-is-a-dead-duck/. The current one has my thoughts on the cycling revival: stillborn or a new lease of life for the bike? Let me know if you’d like a sample copy. https://www.chartist.org.uk/carry-on-cycling/

Still in print: previous publications

The Settle-Carlisle Railway (2019) published by Crowood and available in reputable, and possibly some disreputable, bookshops price £24. I have a few which I can offer with £4 postage. It’s a general history of the railway, bringing it up to date. It includes a chapter on the author’s time as a goods guard on the line, when he was based at Blackburn in the 1970s. The book includes a guide to the line, from Leeds to Carlisle. Some previously-unused sources helped to give the book a stronger ‘social’ dimension, including the columns of the LMS staff magazine in the 1920s. ISBN 978-1-78500-637-1

With Walt Whitman in Bolton – Lancashire’s Links to Walt Whitman. This charts the remarkable story of Bolton’s long-lasting links to America’s great poet. Normal price £10.00, selling for £5.00. Bolton’s links with the great American poet Walt Whitman make up one of the most fascinating footnotes in literary history. From the 1880s a small group  of Boltonians began a correspondence with Whitman and two (John Johnston and J W Wallace) visited the poet in America. Each year on Whitman’s birthday (May 31) the Bolton group threw a party to celebrate his memory, with poems, lectures and passing round a loving cup of spiced claret. Each wore a sprig of lilac in Whitman’s memory.

of Boltonians began a correspondence with Whitman and two (John Johnston and J W Wallace) visited the poet in America. Each year on Whitman’s birthday (May 31) the Bolton group threw a party to celebrate his memory, with poems, lectures and passing round a loving cup of spiced claret. Each wore a sprig of lilac in Whitman’s memory.

The group was close to the founders of the ILP – Keir Hardie, Bruce and Katharine Bruce Glasier and Robert Blatchford. The links with Whitman lovers in the USA continue to this day. Later this summer (see above) I’ll be bringing out an expanded version which has more on the wider political context – Unlikely Pioneers: Walt Whitman, The Bolton Boys and Northern Socialism.

Northern Rail Heritage A short introduction to the social history of the North’s railways. Very few left but I’m planning a new, updated edition. Hopefully will be available from February 2021.

The North ushered in the railway age with the Stockton and Darlington in 1825 followed by the Liverpool and Manchester in 1830. But too often the story of the people who worked on the railways has been ignored. This booklet outlines the social history of railways in the North. It includes the growth of railways in the 19th century, railways in the two world wars, the general strike and the impact of Beeching.

Will Yo’ Come O’ Sunday Mornin? The Winter Hill Mass Trespass of 1896. The story of Lancashire’s Winter Hill Trespass of 1896. 10,000 people marched over Winter Hill to reclaim a right of way. Price: £5.00 (not  many left). The Kinder Scout Mass Trespass of 1932 was by no means the first attempt by working class people to reclaim the countryside. Probably the UK’s biggest-ever rights of way struggle took place on the moors above Bolton in 1896, with three successive weekends of huge demonstrations to reclaim a blocked path. Over 12,000 took part in the biggest march.

many left). The Kinder Scout Mass Trespass of 1932 was by no means the first attempt by working class people to reclaim the countryside. Probably the UK’s biggest-ever rights of way struggle took place on the moors above Bolton in 1896, with three successive weekends of huge demonstrations to reclaim a blocked path. Over 12,000 took part in the biggest march.

A new supply has been found and is available price £5 plus postage (free local delivery)

Ordering:

Please use this link:

http://lancashireloominary.co.uk/index.html/order-form

Other titles still available:

Socialism with a Northern Accent (Lawrence and Wishart)

This was my take on a progressive Northern regionalism, with a foreword by the much-maligned but admirable guy, John Prescott. Time for a new edition – working on it

Railpolitik: bringing railways back to communities (Lawrence and Wishart)

This is an overview of railway politics from the early days to semi-monopolies and current arguments for nationalisation, or co-operative ownership?