From Bolton to Bethesda: Lancashire children and the Penrhyn Lock-Out

“….the daylight is dying over the mountains and the sunset is fair on bonny Bethesda – bonny Bethesda where babes want for bread. As I write, I see before me once again the faces in the mass meeting, the earnest, honest, resolved face, and the vast throng stands up and sings, fervently and pathetically, in Welsh, ‘Land of My Fathers’.[1]

A unique example of children’s solidarity

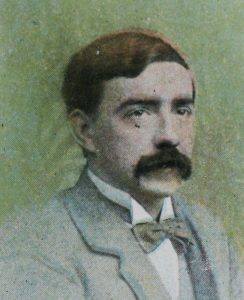

The active involvement of children in popular politics has been little-researched. One of the most remarkable examples occurred in the early years of the 20th century, during the long and bitter Penrhyn Lock-Out, in North Wales. Bolton writer and socialist Allen Clarke, through his ‘Children’s Column’ in Northern Weekly, played the key role in galvanising a unique campaign, mobilising hundreds of Lancashire boys and girls to help their sisters and brothers in Wales.[2]

Barrow Bridge was at the heart of the campaign, as the location for Clarke’s biggest-ever event – ‘The Teddy Ashton Picnic’ (Clarke’s nom-de-plume for his Lancashire dialect writings) – organised to raise funds for the locked-out quarry workers. At a time when children and young people are becoming active in fighting climate change, recalling earlier examples of children’s engagement in radical causes is important. The story of Lancashire children’s support for their sisters and brothers in Wales during the Penrhyn Lock-Out has been hidden from history; it should be celebrated.

Britain’s longest and most bitter industrial dispute

The enormous Penrhyn slate quarries at Bethesda in North Wales were the scene of what was one of the longest and most bitter struggles in British working class history. It began on November 22nd 1900 with the victimisation of a small group of quarrymen. It quickly spread to the entire quarry complex and became a fight for trade union rights, better working conditions and improved wages.[3]

Lord Penrhyn refused to even meet the men’s representatives in the North Wales Quarrymen’s Union, and kept them locked out for three years. Of the 2,800 men who came out, over a thousand never returned. The village of Bethesda was decimated – shops closed down, houses became empty and families were split up.

Although the men were ultimately defeated, Lord Penrhyn paid a high price. Never again did his quarries achieve their previously unrivalled position in the world slate market.

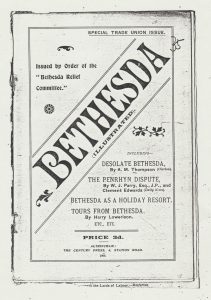

There was wide public sympathy for the men. What they were demanding was only what was enjoyed by workers in much of British industry, by the turn of the century. Popular daily papers like The Morning Leader and Daily News publicised the workers’ case and raised money to ward off the creeping starvation that was looming over Bethesda. The union, and the Penrhyn Relief Committee, appealed for help to trades unionists and the public at large. The socialist movement did much to build support at a local level in many towns and cities across Britain.

Bolton to the fore

Perhaps nowhere was that support stronger than in Bolton. The local Labour Church, led by the veteran radical and friend of Clarke’s, James Sims, played a key role in organising support.

The help that came from working class families, including children, was remarkable. It was the support from local children, many of whom were working in the mills as ‘half-timers’, which marked out Bolton’s contribution as exceptional. [4]

Alongside the Labour Church, Allen Clarke and his newspaper Teddy Ashton’s Northern Weekly, did much to galvanise support. It had a ‘children’s column’ by Allen Clarke, writing as ‘Grandad Grey’, which encouraged young readers to contribute articles and poetry, and – as we shall see – get practically involved in the struggle.[5]

Local support grows

By the spring of 1901 it was clear that the Penrhyn Lock-Out would be a long and painful battle. Throughout Britain, trades unionists, socialists and other well-wishers were sending funds to help families in Bethesda. Bolton was at the forefront. One particular event helped to build local support to a high level. This was the great ‘Teddy Ashton Picnic’ held at the local beauty spot of Barrow Bridge, on May 11th 1901. He had begun planning the event some weeks earlier, promoting it through his Northern Weekly.

The great Barrow Bridge Picnic

Clarke had a ready-made audience for his picnic in aid of Bethesda, through his newspaper. He built up support for the event through local groups like the Labour Church and arranged special reduced rate tickets with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. Wagonettes were on hand at Trinity Street station to take some of the visitors the three miles to Barrow Bridge, though most probably walked.

The picnic attracted a crowd of over 10,000, with people coming from all over Lancashire. There was entertainment provided by the local Clarion Choir and other musicians. The village institute laid on food to cater for the enormous crowds and quickly sold out. The village shop produced special ‘Barrow Bridge Rock’ which popular with the children. There was even a ‘moving picture show’ by local impresario Fenton Cross.

The local constabulary had expressed concern to Clarke and the organisers that such a large crowd might cause disorder. In the event, a policeman turned up at Clarke’s house the following day to thank him for a well-organised and entirely peaceful gathering! There wasn’t a trace of litter.

Support from the unions

The trades unions of Bolton responded magnificently to the quarrymen’s appeal. Nineteen unions in the town contributed money, with the powerful spinners’ union contributing £150 and the Card and Blowing Room Operatives a further £150, with an additional £50 from the local branch. Individual branches, such as the Bolton Spinners’ Atlas no. 1 Mill, contributed smaller amounts. Engineers, bleachers and dyers, carters, hairdressers, railwaymen, miners, printers and even life assurance agents sent in substantial sums.[6]

The choral concerts

In June 1901 the Bethesda Choir made their first visit to Bolton as part of a national fund-raising tour. They were back the following week, performing at a concert in the Temperance Hall organised by Bolton Trades Council and the local Co-operative Society. The officers of the Trades Council spoke, alongside by the president of Bolton Co-operative Society. They were followed by the Liberal MP George Harwood and Bolton socialist activist Fred Brocklehurst. James Sims did most of the promotion for the concert, selling tickets and organising publicity in conjunction with Clarke’s Northern Weekly. The event was a great success and the choir were asked to come back for a further concert.

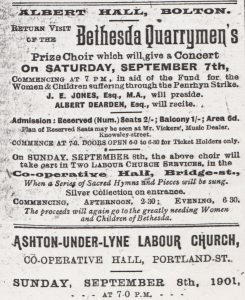

This time, the huge Albert Hall was the venue with reserved tickets selling for 2 shillings for the best seats down to sixpence. J. E. Jones, Headmaster of Bolton School, presided. A dialect recital was given by Albert Dearden. The following day, a Sunday, Bolton Labour Church put on two performances of the choir in the Co-operative Hall, at 2.30 and 6.00pm.

The concerts continued into 1902. By then, Bethesda possessed two male choirs and a ladies’, which visited Bolton in November 1901. One of the male choirs came to Bolton for a weekend of concerts on February 1st and 2nd. The Albert Hall was the venue for the Saturday evening concert and the Temperance Hall hosted the Sunday performances. Both were organised by the Labour Church. Allen Clarke gave an account of the Albert Hall concert in Northern Weekly, commenting on a particularly fine rendition of ‘Ash Grove’.

Barrow Bridge featured once again in the campaign, with a fund-raising concert held in the former Institute on Good Friday, 1902. The Harvey Street Choir, of Halliwell was conducted by Mr F. Hamer. Their performance was followed by readings from the work of Bolton dialect writer J. T. Staton (see Chapter 12). A report in Northern Weekly said that his comic tale, ‘Soup for a Sick Mon’, had the audience in tears of laughter.

The children join in

Following the February concert in the Albert Hall, Clarke hit on a novel idea to involve young readers of his paper. He ran a children’s column in Northern Weekly, writing as ‘Grandad Grey’. Some of the young readers of his column had parents who were socialist activists. Towns such as Bolton, Darwen and Burnley had a flourishing socialist culture, with active branches of the Independent Labour Party, Social Democratic Federation and Labour Church. There were ‘Socialist Sunday Schools’ which children attended and learned a socialism that was ethical, compassionate and inclusive. Clarke’s Northern Weekly was a non-aligned labour/socialist paper which did much to popularise a distinctive ‘Northern’ socialism.[7]

At the beginning of February he published his first appeal, headed ‘I WANT YOU TO HELP’. He gave a simple but moving account of the struggle so far, and asks:

“Now I want the children of England – and especially the children who read The Northern Weekly – to help the children of Bethesda. I want you to collect money for them. I want you to collect old clothes and shoes, and shirts, stockings etc., from your neighbours and friends; then we’ll send the money and clothes to the poor children of Bethesda. For we must not let the big lord beat them and their families.”

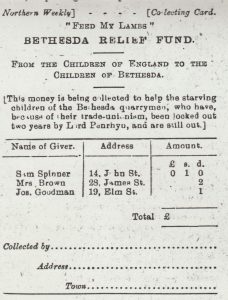

He showed an example of a collecting card which he had printed, “filling in a few names to show you how to do it.”[8] The collecting card was headed ‘FEED MY LAMBS – Bethesda Relief Fund’ and was sub-titled ‘From the children of England to the children of Bethesda’.

The card said “This money is being collected to help the starving children of Bethesda quarrymen, who have because of their trade unionism been locked out for two years by Lord Penrhyn and are still out.”

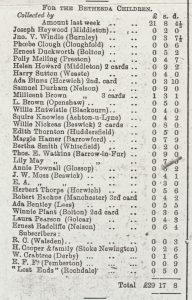

The response was remarkable. Within a week 26 children had returned completed cards, with monies totalling £10.10.7. Most of the children were from the Bolton area, though others wrote in from Heywood, Ashton, Rochdale, Oldham and other Lancashire towns. Interest extended into the West Riding of Yorkshire, with children in Huddersfield and the Colne Valley involved in the collections.

Rachel Baxendale from Darwen replied to the appeal within two days:

“Dear Grandad, This is the first time in my life (that I have written a letter to a newspaper – ed.), but my dada said he would help me if I would try…We have read about the Bethesda children and we are sorry for those two little boys that had only one short for them both. We would like to help them if we could, and if you could please send us one of your collecting cards we will try. I may say that I am eight years old and in the second standard.”

Yours truly, Rachel Baxendale”[9]

The following week, her contribution of 6s 5d was acknowledged in The Northern Weekly.

The money collected was sent on to the Rev. Lloyd, secretary of the Relief Committee. In his replies thanking the children for their great efforts he referred to the plight of some of the families:

“…a family of nine – father, mother and seven children. The father is in poor health and the mother has to keep some of the youngest children in bed to save their breakfasts. The Relief Fund cannot give more than 7s a fortnight on average.”

Lloyd had a special message for the young readers of Northern Weekly:

“…our sincerest thanks to you on behalf of the Bethesda children for sympathising with them, who suffer through no fault of their own. They join their fathers and mothers in the processions of the workmen along the streets of our town carrying small banners and flags with Welsh inscriptions thereon, which translated mean ‘It is better to die a soldier than live a traitor’. Thus they take part in one of the bitterest, longest labour struggles ever known, whose consequences in want and poverty are so appalling. Your subscriptions will cheer them up, I know, and will gladden the hearts of their parents.”

Susie, Harold, Martha, Ezra and Lily

Susie Lord was a 13-year old girl working at Whitewell Slipper Works at Waterfoot in Rossendale.[10] She wrote to The Northern Weekly to say that a copy of the paper had been passed round the machine room and the girls decided to have a collection. It raised £1 15s 6d, and Susie became a regular contributor to the fund. The girls in the adjoining ‘Turnshoe and Clicking Rooms’ contributed a further 10s 6d.

Harold Hargreaves, of Barrowford, wrote in to say “The weather is very nice for sliding, but I have given it up to go collecting for the children.” Martha Smith, of Walkden, wrote to ‘Grandad Grey’ telling him “I am sure Lord Penrhyn is not worthy of the name of man or he would not force little innocent children to starve and clem.”

Ezra Brittan, age 11 of Oldham, said he was “very sorry to think that children have to suffer through a bad man, even if he is a lord..if you ever come to Oldham, come to our house for tea – you will be welcome.”

One of the most touching letters published in Northern Weekly came from ‘Lily’, daughter of one of the locked-out quarrymen. It was headed ‘A Letter from a Bethesda Child’:

“Dear sir, I take this opportunity to thank you for your kindness, and to thank the children, who are collecting on behalf of the poor children at Bethesda, who have suffered so much during this cold weather. My father was at the mass meeting when Mr Lloyd read out some of the children’s letters, and they were moved to tears when the sympathetic letters were read to the meeting. I am very glad to know you take so much interest in our cause, and that you intend to send an excursion here this summer, and I I would like to see some of the children when they come to Bethesda. We live on the top of a hill close to Bethesda, and my father is working at present in a slate quarry at the foot of Snowdon, and goes away early every Monday morning and comes back on Saturday, to spend the Sunday with us, and I don’t like to part with him every Sunday night. I hope you will accept my sincere thanks, on behalf of the children, and that you will accept my mistakes, as I am a 9-year old Welsh girl, who does not know to write English properly. You may print this letter in a corner of your paper, if you think it is good enough.

Yours truly, Lily”[11]

Holidays in Bethesda

The excursion which Lily refers to was part of one of the ideas to assist the quarrymen’s families. Organisations such as local co-operative societies and The Northern Weekly arranged holidays to Bethesda, with accommodation provided in the quarrymen’s cottages.

At Whitsun 1902 Clarke organised a cycle trip from Bolton to Bethesda, offering 25s for full board for the week, or 5s for a day. The route was out via Chester and the coast, returning via an inland route through Betws-y-Coed and Wrexham. He extolled “the cleanliness and sweet homeliness of the people” and the fine mountain scenery, walks, fishing and fresh air.

He produced some of his most powerful journalism during his Bethesda visits. In a full page editorial in The Northern Weekly headed ‘Where Babes Want for Bread’, he contrasts the beauty of Snowdonia with the suffering taking place there:

“Beautiful are the mountains about Bethesda, beautiful are the vales and waters, beautiful the lanes and trees, beautiful the white lambkins on the green hillsides – but blighted are the homes of the workers in the midst of this because one man has hardened his heart, because one man selfishly holds a piece of Nature that neither he, nor his ancestors, ever made, and to which he has really no more sole right than the humblest drudge in this village of Bethesda, over which he is Lord till death reduces him to his deserved level.”

The messianic Christian socialist tone continues to the end of the piece:

“I must finish now. As I cease the daylight is dying over the mountains and the sunset is fair on bonny Bethesda – bonny Bethesda where babes want for bread. As I write, I see before me once again the faces in the mass meeting, the earnest, honest, resolved face, and the vast throng stands up and sings, fervently and pathetically, in Welsh, ‘Land of My Fathers’. And I say to myself, as the sunset lights end, and shadows fall across the garden in front of the cottage, and through the window upon my paper, ‘May the glorious morning soon come, the morning of rejoicing for Bethesda!”

The end

That morning never came. The lead story of The Northern Weekly for October 17th 1903 was headed ‘A Long and Bitter Lock-out’. It was a valiant attempt to rally support for what was a dying cause. A few weeks later it was all over, with only a selected number of the men being allowed to return to work.

The children’s fund raised £147 9s 5d. It was a small sum in comparison to the thousands raised by newspaper campaigns such as that mounted by the Morning Leader and the contributions from the big unions. But in many ways it is more remarkable. The children who contributed were from ordinary working families. Some of them were half-timers in local mills and factories. The letters of the young children, from ages of seven or eight, show an amazing degree of maturity and compassion.

Perhaps some of the children involved in the Bethesda appeal went on to become leaders in their communities, or in the socialist and trade union movement. We know little about them. Nor do we know if the friendships created during the lock-out, through the visits of the choirs to Lancashire and the excursions to Bethesda, resulted in continuing links between towns like Bolton and Bethesda. It would be good to think that they did.

This article is taken from my book ALLEN CLARKE: Lancashire’s Romantic Radical (published 2021 by Lancashire Loominary)

[1] Allen Clarke in Teddy Ashton’s Northern Weekly May 31st 1902

[2] This essay was first published in Bolton People’s History in 1984 as Feed My Lambs: Bolton Kids and the Penrhyn Lock-Out. It has been updated with some additional information added.

[3] For a full account of the lock-out and the wider political and social context, see R. Merfyn Jones The North Wales Quarrymen 1874-1922, Cardiff, 1982

[4] The ‘Half-Time System’ forced working class children to work half-time in mills and factories and spend the rest of their day at school. It was prevalent in the textile districts of Lancashire and Yorkshire and was finally abolished in 1918. See Edmund and Ruth Frow The Half Time System of Education, Manchester 1970

[5] See Lancashire’s Romantic Radical: The Life and Work of Allen Clarke/Teddy Ashton

[6] The Hairdressers’ Union contributed £21.10s. Other local donations included Gas Workers £3, Typographical Association £1, Wheelwrights £10, Atherton Miners £2, Wharton Hall Miners £2, Lostock Railwaymen £1, Saddlemakers £1, Carters £5, Tape Sizers £2 1s, Engine and Iron Grinders £2.

[7] See Paul Salveson Walt Whitman and the Religion of Socialism in the North of England (forthcoming, 2020/1)

[8] Northern Weekly February 8th 1902

[9] Northern Weekly February 15th 1902

[10] The Rossendale Valley was noted for its footwear industry, particularly slipper manufacture. Large numbers of female labour, including half-timers such as Susie, were employed in the industry. It was highly unionised though I am not aware of whether children were admitted into the union.

[11] Northern Weekly February 22nd 1902