The Northern Salvo

A gradely Salvo for gradely folk* Incorporating Weekly Notices, Sectional Appendices, and Northern Weekly Salvo

Published at Station House, Kents Bank, Lancashire-North-of-the-Sands, LA11 7BB and at 109 Harpers Lane, Bolton BL1 6HU, Lancashire

email: paul.salveson@myphone.coop

Publications website: www.lancashireloominary.co.uk

No. 324 December 2024

Salveson’s half-nakedly political digest of railways, tripe and secessionist nonsense from Up North.

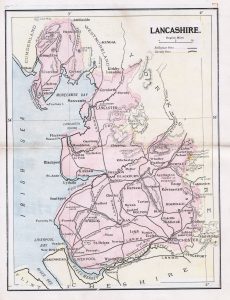

Celebrating Lancashire Day

Greetings on Lancashire Day, November 27th – and by Lancashire I mean ‘real Lancashire’ stretching from the Mersey to the Lakes, not what the media imagines it as today. This Salvo, slipped in between  November’s and the Christmas Salvo, out in mid December, has a predominantly Lancashire flavour but hopefully those unfortunate enough not to live in the County Palatine will still find something of interest. I’ve done a slightly updated version of my Christmas ghost story (‘Who Signed The Book?’) which some of you may have seen before. I’m working on a new ghost story to feature in the Christmas Salvo, provisionally titled ‘The Crossing Keeper’s Cat’.

November’s and the Christmas Salvo, out in mid December, has a predominantly Lancashire flavour but hopefully those unfortunate enough not to live in the County Palatine will still find something of interest. I’ve done a slightly updated version of my Christmas ghost story (‘Who Signed The Book?’) which some of you may have seen before. I’m working on a new ghost story to feature in the Christmas Salvo, provisionally titled ‘The Crossing Keeper’s Cat’.

*What is ‘gradely’? ‘Gradely’ is a Lancashire term for all that is good, proper and right. There is an old joke about a southerner coming to Lancashire and hearing the word used – but being unable to find it in his dictionary. “That’s because,” he was told, “it’s not a gradely dictionary!” It’s time we re-instated this wonderfully expressive word into our daily speech….

John Prescott: one of us

It’s sad news about John Prescott’s passing, rightly described by The Guardian as a ‘titan of the Labour Movement’. He was a great guy and I enjoyed working with him back in the mid-1990s. Contrary to what a lot of snobbish people (left and right) said, he was an intelligent and thoughtful politician who did as much, if not more, than anyone to get a progressive integrated transport system on the agenda. He brought together a group of transport activists, myself included, to contribute to a collection of essays on transport policy, perhaps unfortunately titled Travel Sickness. A lot of the ideas in there are still very relevant today – let’s hope Louise Haigh and her team learn from the good ideas that were around in the 1990s. You don’t have to go to Dijon to see what works.

He was also passionate about working class history. He kindly wrote the foreword to my book Socialism with a Northern Accent, published twelve years ago. Talking of ‘Labour’s traditional, community-

based values’ he said “These values were born out of the industrial struggle in the North, which was long and bitter. It was working class people who created the trades unions, co-operatives and municipal bodies as foundations of our communities that still endure.” Perhaps the best tribute to him came from a chance conversation I overheard on a train heading to Paddington from Plymouth, years ago during the Blair era. A driver and guard were travelling to London ’on the cushions’ to work something. They were talking about modern Labour politics, not with unbridled enthusiasm I have to say. However, the conversation got on to Prescott and one of them, in a broad West Country accent, said “Well he’s different…he’s one of us.” And he was. Politics is a less interesting place without his brain.

What we’ve achieved – but where are we now?

This is based on the Introduction to my book ‘Lancastrians: mills, mines and minarets’ published by Hurst in 2023. It’s slightly updated: the book itself is still available (see below or from the publisher, Hurst).

Lancashire is a region with a strong identity. Despite attempts to

dismantle much of the historic county, many people in what is now officially Greater Manchester, Merseyside or Cumbria, cling on to their sense of being ‘Lancastrian’.

Before the mid-17th century it was an agricultural society. The ‘county palatine’ had been created in the 14th century and the county developed around a small number of wealthy and influential families and powerful religious settlements. The pre-Industrial Revolution centuries saw the creation of some major religious communities, including Cartmel Priory, Furness and Whalley Abbeys. They’re well worth visiting and can be easily reached by train.

The Lancashire Powerhouse

Lancashire went from being a relatively backward place in terms of industry and learning to become the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution, as well as a cultural centre. It was based on textiles: the creation of a self-confident industrial bourgeoisie drove economic growth. The origins of these entrepreneurs varied. We should beware of the myth that they were all ‘self-made-men’. Yet their achievements in not only industry but also in architecture and culture are enormous.

In these early years, the ‘handloom weavers’ became the intellectual aristocracy of the working class. Many were highly literate, accomplished musicians and botanists. Their contribution to a Lancashire culture cannot be exaggerated; many of their botanical and geological collections survive; their music and literature remains, but is largely unrecognised. The handloom weavers produced many talented musicians. The most well-known were the ‘Larks of Deighn – or ‘The Deighn Layrocks’ from a small weaving community in Rossendale.

Some were skilled instrument makers and performed the works of Haydn in small hillside chapels. Some composed their own hymns and orchestral works. Subsequently, the ‘operative spinners’ in towns such as Oldham, Bolton, Rochdale and Bury were prominent in friendly societies and the co-operative movement.

The Dialect Tradition

Lancashire had a very strong folklore tradition, saturated with references to that characteristically Lancashire creature, ‘the boggart’ – a name that once struck fear into children. Boggarts are not so common nowadays but their reputation lives on in literature and physical features such as Boggart Hole Clough in North Manchester and ‘The Boggart Bridge’ in the grounds of Burnley’s Towneley Hall. Numerous Lancashire houses were reputed to be haunted.

A distinctive Lancashire dialect literature began in the mid-19th century though its roots are earlier. John Collier (‘Tim Bobbin’), from a handloom-weaving community near Rochdale, was the first major writer to set down dialect speech in literature, with his ‘Tummus un Meary’ in 1746. Others followed but it was Edwin Waugh, again from Rochdale, who made the real breakthrough in the 1850s with is poem ‘Come whoam to thi childer an’ me’ – largely thanks to middle class sponsorship. A tradition of Lancashire dialect literature developed during the second half of the century, with poets and prose writers including Waugh, Samuel Laycock, Ben Brierley and other lesser-known working men, mostly from handloom weaving backgrounds. Towards the end of the century a small number of women were writing in dialect, such as Margaret Lahee.

The fight for the right to roam

Lancashire has long had a love of the countryside; an important aspect of the handloom-weaving culture was an interest in botany and herbalism. This combined with an appreciation of the countryside which developed into the organised rambling movement of the late 19th century. Initially this was an urban middle class pursuit but a growing number of working class men and women formed field naturalist societies and also cycling organisations such as the Clarion and numerous local bodies. This could be reflected in class conflict between landowners and the working class – the most notable events being the Winter Hill Mass Trespass of Bolton in 1896 and rights of way struggles in Darwen, Bury and Flixton. Many of the participants of the Kinder Scout Trespass of 1932, including its leader Benny Rothman, were from Manchester and Salford. The modern ramblers’ movement was inspired by Lancastrians such as Tom Stephenson and more generally by the writings of Alfred Wainwright and Jessica Lofthouse.

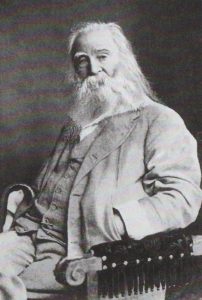

In the late 19th century a small group of Lancastrians developed close links with the great poet of the countryside, Walt Whitman, which continues to this day. Each year admirers of Lancashire poet and singer of the outdoors, Edwin Waugh, celebrate his memory with a walk to Waugh’s Well, on the moors above Rossendale. The Winter Hill Mass Trespass is still commemorated in Bolton.

The Lancashire musical tradition was partly born of its strong religious culture but also of these informal working class musical groups. By the middle of the 19th century there were choirs and orchestras of national repute. The Halle Orchestra was formed in 1857 but was preceded by the Manchester Camerata. In Liverpool, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic is one of the oldest orchestras in the world, being formed in 1840. Alongside the classical tradition, Liverpool pubs resounded to sea shanties, often with Liverpool themes.

Food and drink

Lancashire, like most parts of Britain, had a distinct food and drink culture which continues to the present day. Bury is of course famous for its black puddings which have an enduring popularity which perhaps tripe doesn’t enjoy. Lancashire has outstanding cheeses, simnel cake and of course hot pot. What has survived, what hasn’t? A new generation of brewers have revived some old Lancashire favourites such as ‘dark mild’, and ‘whoam-brewed’ ale is celebrated in many dialect poems. Fitzpatrick’s sarsaparilla has experienced a revival and the last surviving ‘temperance bar’ in Lancashire – at Rawtenstall – is flourishing.

A Lancashire Intelligentsia

A central feature of Lancashire’s growth into a powerful Northern region was the formation of a distinct intelligentsia, partly but not entirely based on the emerging universities of Manchester and Liverpool. The industrial bourgeoisie was far from being simply a class of money-making philistines: industrialists like Leverhulme had a strong commitment to the arts and endowed galleries and museums. This reflected their own roots within Lancashire.

There was also a network of ‘learned societies’, mostly but not entirely comprising middle class men, some of whom had achieved wealth through textiles or engineering. The Manchester Literary Club is a good example; by the end of the 19th century many smaller towns had their own literary and scientific societies, including Burnley, Warrington, Darwen, Leigh, Bolton, Bacup and elsewhere. The many local co-operative societies had their own members’ libraries; Rochdale’s had a stock of several thousand books. For middle-class readers, their needs were catered for by private subscription libraries such as the still-thriving Portico in Manchester (est. 1802). The growth of municipal libraries is an important part of Lancashire’s cultural history. At the same time, Lancashire developed a strong local press in the 19th century, with larger towns often having daily newspapers which reflected political loyalties (usually, Liberal and Conservative). Most local newspapers promoted local writers, often serialising novels and short stories and publishing local poetry. Warrington had its own literary magazine in the early 1900s called ‘The Dawn’. Locally-based publishers such as Abel Heywood and John Heywood of Manchester, and Clegg of Oldham, were crucial to the development of a Lancashire literature.

Lancashire authors and engineers

Lancashire was a much-written about county in the 19th century but few novelists were local. A remarkable exception is Elizabeth Gaskell who wrote powerful fiction about life in industrial Lancashire. The Lancashire Authors’ Association was formed in Rochdale in 1909 and was an uneasy alliance of working class writers like Hannah Mitchell and Allen Clarke with middle class literati. It still exists with an extensive library now based at the University of Bolton. Twentieth century Lancashire writers included Walter Greenwood, Harold Brighouse, Bill Naughton and William Holt. Contemporary writers include Jeanette Winterson (exiled in London) and Salford poet John Cooper-Clarke (a modern-day Edwin Waugh?).

Lancashire developed a pioneering role in engineering, initially in relation to textile machinery but broadening out into other fields and building a world-wide market. Engineers from Bolton and Oldham were instrumental in creating Russia’s cotton industry and many stayed, marrying Russian women. The role of the British Empire is crucial in Lancashire’s development and this was reflected in areas such as textile design. The growth of Barrow-in-Furness was based around shipbuilding for the Royal Navy and its associated iron and steel industry.

Railway pioneers

Whilst the railway network initially developed thanks to the genius of the North-east based Stephensons, Lancashire became a centre of railway engineering excellence with major railway factories in the Manchester area (Gorton, Patricroft) and – later – Horwich. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world’s first inter-city railway, though the Bolton and Leigh beat it by two years as the first public railway in Lancashire. The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway was an example of a powerful regional business with its headquarters in Manchester. The Furness Railway was another example of regional enterprise which made the most of opportunities in both freight, passenger services and niche operations in tourism.

Municipal pride

The architecture of Lancashire reflected its industrial achievements, with the development of distinctive architectural styles in cotton mills, warehouses and engineering factories. These often had classical references, reflecting the sense that Lancashire was the ‘new Athens’. The Co-operative movement, first established in Lancashire, developed a distinct architectural style for its stores, many of which remain. The growth of municipal power was reflected in opulent town halls, such as Rochdale, Manchester, Liverpool, Bolton, Barrow and Preston. Smaller towns such as Farnworth, Radcliffe, Hindley, Rawtenstall and Heywood had strongly independent administrations with substantial town halls that reflected this.

The arts tradition is extensive and well-documented. Lowry is important, but so too his predecessors such as Adolphe Vallet and Walter Crane – and Lowry’s successors including Theodore Major, Helen Clapcott, Geoffrey Key and many others. There was a distinctive ‘Lancashire Art’ movement which remains vibrant today, supported through outstanding institutions in Manchester, Liverpool, Preston, Warrington, Bolton and other towns.

A Lancashire politics

Lancashire was at the forefront of the rise of the socialist movement in the last decade of the 19th century. This had a strong cultural element with the formation of socialist clubs with their own choirs, field rambling clubs and a distinct socialist literature, often using dialect, in the work of Allen Clarke, Ethel Carnie, Sam Fitton and others. On the opposite end of the spectrum there was the phenomenon of ‘Clog Toryism’ with some Lancashire towns retaining strong loyalties to the Conservative Party – a phenomenon that has been re-awakened with the ‘red-wall Tories’ elected in 2019. Several present-day Conservative MPs support ‘Lancashire’ cultural bodies including Friends of Real Lancashire and The Lancashire Society, though they also have patrons amongst Labour MPs and peers.

Political club culture grew rapidly from the 1890s and many fine buildings remain (often turned over to other uses) that were once Conservative or Liberal ‘working men’s clubs’. Labour clubs came later and were mostly less opulent. The Bolton Socialist Club, founded in 1895 survives – since 1905 housed at 16 Wood Street, Bolton, birthplace of Lord Leverhulme! Nelson’s Unity Hall, opened in 1907, has recently been refurbished and features displays of the early socialist movement in East Lancashire. Sadly, the grand Conservative Club in Accrington has been demolished.

In between Conservative and Labour, Lancashire had a distinct Liberal politics, embodied in people such as Thomas Newbigging, historian of Rossendale and radical Liberal in the 1880s, Solomon Partington of Bolton who led the Winter Hill Mass Trespass, and Samuel Compston, leader of East Lancashire Liberalism and enthusiast for Lancashire history and culture. It linked in to strong traditions of Nonconformity and was particularly strong in Rossendale and East Lancashire. This ‘Lancashire Liberal’ tradition has all but disappeared though Liberalism made something of a comeback in the 2024 General Election in some parts of the region.

Religious identity was often reflected in political loyalties and through the 19th century there was a close correlation between church-going Anglicans and the Conservative Party, with various hues of Nonconformity tending strongly towards Liberalism. The growing Irish communities in the second half of the 19th century were sometimes Liberal but tended to switch to Labour in the 20th century.

Trades unions developed during the 19th century; most were local or regional in nature. For much of the 19th century the main cotton towns had their own independent unions reflecting hierarchies within the industry – spinners, card room workers, weavers and many more. The Lancashire miners’ union remained independent throughout most of the 19th century and continued as a highly devolved regional body up to and after the Miners’ Strike of 1984/5, when the Lancashire NUM took a different stance to the national (Yorkshire-led) leadership.

Sporting Lancashire

Sport was a major part of Lancashire identity – though there were few specifically ‘Lancashire’ sporting bodies, with the notable exception of country cricket. Towns had professional football and Rugby League clubs from the late 19th century and they became symbols of local pride. Very often there was a distinction between ‘coal’ and ‘cotton’ towns with Rigby League tending to predominate in mining areas (Leigh, Wigan, St Helens and Salford) while cotton towns tended to be more football-oriented (Bolton, Blackburn, Preston, Burnley). But there were exceptions, with Oldham and Rochdale tending to be rugby towns. The two major cities – Liverpool and Manchester – were and still are primarily football towns, each with rival local teams. Manchester City remains true to its Lancashire roots with the red rose of Lancashire featuring in its crest. Lancashire country cricket is still based at Old Trafford.

Lancashire at war

The county has a strong military tradition, with notable regiments including the Lancashire Fusiliers (commemorated in its own museum in Bury), the East Lancashire and the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiments. The horrendous carnage in the First World War was highlighted by the wiping-out of the ‘Accrington Pals’. There is a moving memorial to ‘the Pals’ in the town and displays in the town hall and heritage centre. Other towns as well as Bury had substantial barracks, including Ashton-under-Lyne and Preston. One of the most outstanding monuments to the horror of war is the statue of the blind soldiers – ‘Victory over Blindness’ – outside Manchester Piccadilly station. The changing way in which war has been commemorated across Lancashire is reflected in its art and historical interpretation in museums, including the Imperial War Museum (North) at Salford Quays.

Alongside the formal military tradition, many Lancashire men joined the International Brigades to fight in the Spanish Civil War and are celebrated with memorials in Manchester, Bolton and Wigan.

Lancashire women

In the 19th century it was the norm for Lancashire working class women to do paid work – notably in the textile industry, with women predominating in weaving and also ‘unskilled’ parts of the spinning process. They also worked in coal mining, in later decades on the surface as ‘pit brow lassies’. Both middle and working class women were actively involved in the campaign for women’s suffrage – Oldham mill girl Annie Kenney played a major role and the Pankhursts were of course Manchester-based. Mrs Marjory Lees, wife of one of Oldham’s major cotton magnates, was a dedicated supporter. Many female cotton workers were involved in the campaign for the vote, organised by the North of England Women’s Suffrage Society.

Lancashire has long had a flourishing ‘voluntary’ tradition, reflected in thousands of clubs and societies dating back to the 18th century in many cases. The Co-operative movement, begun in Rochdale, is an example of working people getting together and creating their own institutions, which have endured – despite many changes. Friendly societies, trades unions, burial clubs and building societies are examples of the ‘voluntary’ culture, as well as a plethora of local literary and scientific societies which flourished in most towns and villages, Many still do.

Sing as we go: music in Lancashire

Lancashire became famous for its popular music – George Formby, Gracie Fields and Frank Randall became household names well beyond Lancashire in the 20th century. It was also home to one of the country’s greatest opera singers, the Leigh miner Tom Burke, who had unfulfilled ambitions to set up a ‘Lancashire Opera Company’. Lancashire produced some important composers including William Walton, Thomas Pitfield, Peter Maxwell-Davies and Harrison Birtwistle. The Manchester-based Royal Northern College of Music and Chetham’s College continue to produce great music and musicians.

The second half of the 20th century saw Lancashire at the forefront of a revolution in music, led by the Beatles but including Manchester and Salford bands. Later, Tony Wilson almost succeeded in making Manchester the cultural capital of Britain through his various projects including Factory Records and The Hacienda Club. Interestingly, Wilson was a passionate ‘Lancastrian’ and made serious efforts to revive the flagging fortunes of the east Lancashire cotton towns, creating the ‘Pennine Lancashire’ brand. In theatre, talented writers such as Shelagh Delaney pioneered what was derisively called ‘kitchen-sink drama’ but reflected real life in Northern working class communities. The remarkably popular TV series Coronation Street reflects the changing cultural mores of Lancashire over seventy years.

It is more difficult to argue for a specifically ‘Lancashire’ film industry. However, Lancashire was the setting for some outstanding films in the 1960s, such as Spring and Port Wine and The Family Way. There are outstanding Northern film-makers and a growing number of small film studios and companies.

New Lancastrians

Successive waves of migration to Lancashire have created a much more diverse culture – and Lancashire cultural identity. Towns such as Oldham, Rochdale and Bolton have flourishing Asian dance troupes, musicians and singers. To an extent, the ‘new Lancastrians’ in some of Lancashire’s Asian communities have become more ‘Lancashire’ than the rest of us, with strong Lancashire accents heard in the Asian neighbourhoods of many Lancashire towns.

The Irish immigrants of the 1840s, escaping famine, created large and often very poor Irish communities in many Lancashire towns, and there were often outbreaks of anti-Irish hostility in the mid to late 19th century. Jewish migrants arrived in Lancashire in the late 19th century and early 20th century, mostly settling in Manchester. The Manchester Jewish Museum is a superb celebration of Jewish life and the contribution of Jewish people to Manchester life and culture. Later refugees from war and oppression included German Jews in the 1930s through to post-war waves of immigration from eastern Europe, Asia and Africa.

A modern and progressive Lancashire

Can a 21st century Lancashire can be re-born? Towns like Bolton, Wigan, St Helens and further north in Barrow and Ulverston retain a strong Lancashire identity, despite attempts to destroy it. Is it destined to remain a nostalgic and conservative sub-culture, steadily disappearing, or can it be re-created as a modern and inclusive identity reflecting the demographic changes of the last sixty years?

A Lancashire Manifesto

Lancashire and Yorkshire both have strong identities and despite historic rivalries, we have more in common, as Jo Cox would have said, than what divides us. Yet while our Yorkshire neighbours are building up momentum for a ‘One Yorkshire’ region, Lancashire is lagging behind. On Lancashire Day 2024, I’m arguing for a re-united Lancashire, with its own democratically-elected assembly, based broadly on its historic boundaries but looking to the future for a dynamic and inclusive county-region that could be at the forefront of a green industrial revolution. It isn’t about creating top-down structures but having an enabling body that can help things happen: in business, arts, education and other fields. As well as a new county-region body to replace the mish-mash of unelected regional bodies and mayors with little accountability, a re-united Lancashire also needs strong local government (that is genuinely local) working co-operatively with the communities it serves and a vibrant economy that is locally based where profits go back into the community.

Now read on…..http://lancashireloominary.co.uk/index.html/lancashire-re-united

Who Signed the book? A Christmas railway ghost story

This was first published in ASLEF’s Locomotive Journal in December 1985 and was subsequently republished in my collection of short stories, Last Train from Blackstock Junction, published by Platform 5 in 2023. The story is set in the mid-1980s at a remote signalbox on the Bolton – Blackburn line. The link is here:

Lancastrians: Mills, Mines and Minarets

Thanks to historians Alan Fowler and Robert Poole for recent positive comments about the book. In the current North West Labour History Journal, Alan wrote: “The variety of topics is one of the appealing features of the book. It is some time since we had a history of the county, so this account is very welcome, and it reminds the reader of the significance of the county in the UK, one often forgotten by London or Oxbridge-based historians….I hope many readers of the Journal will read it.”

I’m still getting invited to do talks on my ‘Lancastrians’ book. I’ve done several during the Autumn including Chorley Family History Society and Probus clubs in Preston and Leyland (actually on Walt Whitman’s Lancashire links, which feature in the book).

The book is hardback, price £25. Salvo readers can get it post free directly from me:http://lancashireloominary.co.uk/index.html/order-form

Other Lancashire books still in print (at gradely prices)

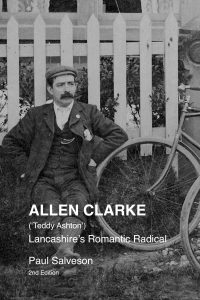

ALLEN CLARKE: Lancashire’s Romantic Radical £5.99 (normally £18.99)

Moorlands, Memories and Reflections £15.00 (£21.00)

Last Train from Blackstock Junction (published by Platform 5 Books). A collection of short stories about railway life in the North of England. Salvo readers can get the book at a specially discounted price, courtesy of Platform 5 Publishing. Go to https://www.platform5.com/Catalogue/New-Titles. Enter LAST22 in the promotional code box at the basket and this will reduce the unit price from £12.95 to £10.95.

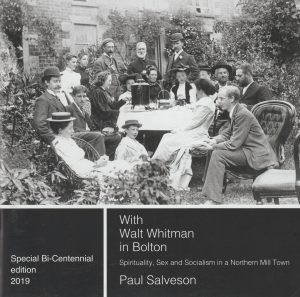

WITH WALT WHITMAN IN BOLTON

This has been out of print for a few months but I’m doing a new edition, only very slightly revised an updated. It will be available from late November, price £12 (including postage). Salvo readers can email orders through.

[1] For a recent general history of Lancashire see Stephen Duxbury, The Brief History of Lancashire (The History Press, 2011)

[2] See John Walton A Social History of Lancashire (Manchester University Press, 1980) for a thorough discussion of the origins of the Lancashire industrial bourgeoisie

[3] Roger Elbourne, Music and Tradition in Early Industrial Lancashire 1780 – 1840 (D.S. Brewer for Folklore Society, 1980)

and religion. It explores the Lancastrians who left for new lives in America, Canada, Russia and South Africa, as well as the ‘New Lancastrians’ who have settled in the county since the 14th century. There are about forty ‘potted biographies’ of men and women who have made important (but often neglected) contributions to Lancashire.

and religion. It explores the Lancastrians who left for new lives in America, Canada, Russia and South Africa, as well as the ‘New Lancastrians’ who have settled in the county since the 14th century. There are about forty ‘potted biographies’ of men and women who have made important (but often neglected) contributions to Lancashire.

ALLEN CLARKE: Lancashire’s Romantic Radical: a biography of the remarkable Aleln Clarke/Teddy Ashton: dialectw riter, cyclist, socialist, philosopher – and more. £5.99 (normally £18.99)

ALLEN CLARKE: Lancashire’s Romantic Radical: a biography of the remarkable Aleln Clarke/Teddy Ashton: dialectw riter, cyclist, socialist, philosopher – and more. £5.99 (normally £18.99)