Christmas Ghost Story: The First Aid Phantom of Wayoh Sidings

My grandchildren are always meithering me for a ‘ghost story’ this time of year. Well here’s one about a benevolent ghost, or boggart, which featured in something that happened to me a long time ago when I was a young relief signalman in Bolton.

It was December 1966, not long after I’d been promoted from my first signalbox at Bullfield West to a ‘relief’ job, with more money. It involved covering rest days, holidays and sickness at several boxes in the Bolton area, mostly within a mile or so of the station. A couple were more remote; the furthest and most difficult one to reach was Wayoh Sidings, up on the moors between Bolton and Blackburn. The  only way you could reach it was by walking up the line from Entwistle, just over a mile. There was no road access and the other relief men didn’t like it – they couldn’t get there by car. I was young and fit back then and would either walk or even cycle up the path along the line, keeping an eye out for passing trains. If it was wet, most drivers – if you asked them nicely – would drop you off outside the box.

only way you could reach it was by walking up the line from Entwistle, just over a mile. There was no road access and the other relief men didn’t like it – they couldn’t get there by car. I was young and fit back then and would either walk or even cycle up the path along the line, keeping an eye out for passing trains. If it was wet, most drivers – if you asked them nicely – would drop you off outside the box.

Wayoh Sidings was at the summit of the line, the end of a long gruelling climb in both directions. It was a lonely place, with the nearest houses half a mile away near the old quarry on the Roman Road. Beyond the box, going north, the line plunged through a deep cutting and then into the two-mile long Whittlestone Tunnel. In steam days most of the freights would be ‘banked’ by a loco coming up behind the train, from either Bolton or Blackburn. When the train reached Wayoh Sidings the assisting engine would shut off steam and come to a stop by the signalbox, with the signalman changing the points to allow it to  drift back to base. If there was nothing else about, the driver and fireman would park their engine outside and come up for a brew.

drift back to base. If there was nothing else about, the driver and fireman would park their engine outside and come up for a brew.

That was about the only company you’d get, apart from the occasional platelayer. Harold Hodgkiss was the regular man who walked his length every week and would call in to ‘camp’ over a brew of tea.

I was rostered to cover the night turn at Wayoh in the week before Christmas, relieving the regular signalman, Frank Hatton, at 10.00pm. Once you’d got there it was an easy job, just an empty stock for Newton Heath depot about midnight, the Colne ‘papers’ at 4 a.m. and the Heysham – Brindle Heath goods round about six, which was usually banked up from Blackburn. My relief would take over at 6 and I’d ‘caution’ the first up passenger and get a lift back down to Bolton. You could get away with that sort of thing, back then. After signing the Train Register Book it was a case of putting the kettle on and settling down to a good read, maybe with a brief doze before being disturbed by a ‘call attention’ signal for the Colne papers – express passenger, followed by four beats of the bell.

Some of the other relief signalmen didn’t like the place, claiming it was haunted. Jimmy Blackburn said he’d heard a voice calling to him when he was walking up the track from Entwistle, something like ‘get out of the way’ and ‘look out’. As a signed-up Marxist revolutionary, I regarded that as a load of superstitious nonsense.

………………………………….

I’d already done a couple of nights that week before ‘the incident’ happened. It was Thursday December 23rd and it would be the last full night shift before Christmas. Frank, on the afternoon turn, would close the box at 10.00pm Christmas Eve and re-open on the 27th.

The last train from Bolton that stopped at Entwistle was the 8.30 to Colne. I could’ve asked the driver to drop me off at Wayoh but thought I’d call in at Entwistle box and have a brew with Paddy Hanlon, one of the two regular signalmen there. The box was perched above the two ‘fast lines’. Back then there were four tracks between  Entwistle and Wayoh, provided by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to give extra capacity for freight trains. By the 60s there wasn’t much freight, apart from the evening Burnley – Moston on the up line and the Ancoats – Carlisle on the down.

Entwistle and Wayoh, provided by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to give extra capacity for freight trains. By the 60s there wasn’t much freight, apart from the evening Burnley – Moston on the up line and the Ancoats – Carlisle on the down.

Paddy always welcomed a bit of company and the kettle was usually on the boil. I got off the diesel train and waved a cheerio to the Manchester guard, watching the train trundle away up the last bit of the climb towards Wayoh, the red tail light slowly disappearing from view on what was a fine, clear but bloody freezing night. You could see your breath almost freeze when you breathed out.

I jumped down off the platform and crossed the tracks to get to the signalbox steps. “Now then Paddy!” I shouted, so he wouldn’t think it was any unwanted visitor, such as an over-zealous inspector making an out of hours call.

I walked up the flight of stairs and found the door unlocked. The warmth from the stove hit you like a blanket as soon as you stepped in.

“Come in and sit yourself down lad,” said Paddy. “The kettle’s just boiled, here’s a nice cup of tea for ye.”

Like all the boxes in the area, there was an ‘easy chair’ that was the preserve of the resident signalman. There was usually another chair for visitors, not as comfortable but good enough. Decorum usually meant that the visitor would make do with the hard chair but Paddy was a true gent and offered me the easy chair.

“Thanks Paddy, that’s very kind. And here’s a card for you and the family.”

Paddy lived in one of the old railway cottages just beyond the pub, he and his family had been there for a good thirty years after moving from a box in the Manchester area, Collyhurst I think. He hailed from the west of Ireland and had no end of stories about life in ‘the ould country’. He loved the Lancashire moors and was the only applicant for the vacancy at Entwistle when the previous incumbent, Abraham Holroyd, retired.

“So Paul, are you and your young lady all ready for Christmas?” he asked.

“Oh, I think so. We’re going over to Sheila’s mother’s for Christmas Day but we’ll have a quiet time, see the rest of the family on Boxing Day, get out for a walk and take it easy.”

“Aye, it’s a time for family alright,” Paddy agreed. “They say it might be a white ‘un too, some snow forecast for tonight according to the news.”

“Well, it’s looking clear enough now,” I replied, not wanting to get snowed in at Wayoh Sidings for Christmas. “But anyway, I’d better be getting on, Frank will be wondering where I am.”

“Aye, he’s a stickler for punctuality is Frank, and no harm in that, for a signalman,” responded Paddy. “Be careful how you go and mind you don’t come across any of those Lancashire boggarts on the way!”

“I don’t think there’s any chance of that, Paddy, but if I do I’ve a spare copy of The Morning Star I can give them, to demonstrate they’re just an illusion!”

“On your way lad, and have a grand Christmas…just look out for the Burnley-Moston, not had it yet so it might be on its way.”

I left the cosiness of Paddy’s box and walked down the steps into the old goods yard and felt the first flurries of snow coming down. The clear bright sky had clouded over and there was an eerie light across the tracks.

If I walked briskly I’d be there in twenty minutes. The unfenced path ran alongside the up fast line and had been used by generations of railwaymen, and – unofficially – some of the local farmers and quarrymen too.

It started coming down heavily and within a couple of minutes I could hardly see the tracks, let alone the path. To make it worse, I was  walking into the wind, howling down from Whittlestone Head and blowing the snow horizontally. I was struggling to see and the snow felt more like small balls of ice.

walking into the wind, howling down from Whittlestone Head and blowing the snow horizontally. I was struggling to see and the snow felt more like small balls of ice.

I was able to walk forward only by feeling the edge of the ballast to my left, under the rails of the up fast line.

I kept edging forward, stumbling a couple of times, and could just make out the lights of Wayoh Sidings box in the distance, through the blizzard.

Maybe I was getting over-confident; I was getting close when I went over. I hit a bit of redundant rail some dozy platelayer had left lying across the path. All I can recall is falling and striking my head against something hard. Then oblivion.

The next thing I can remember is a loud voice, shouting “come on lad, come on, tha’ cornt lie theer…look out!”

I came back into consciousness and felt a hand tugging at my feet. I became aware of the sound of a steam loco hard at work, and not far away.

It dawned on me that I was lying across the outer rail of the up fast, and the sound I could hear was the late-running Burnley – Moston goods, just passing Wayoh Sidings and a few yards from where I was lying. It was working hard, with the driver probably trying to make up a bit of lost time and get home to Manchester. Up here, he was a long way from Deansgate.

I felt another hard tug at my leg and the next instant the ‘whoosh’ of a heavy steam locomotive rushing by, at very close quarters. I could feel the leaking steam from the engine and the smell of hot oil. Then the clank of wagon after wagon as the train went past, followedby silence. I could also feel a small dog pulling at my trouser leg.

“Are you awreet lad?” a voice asked. “Tha’s just had a close call wi’ destiny!”

I looked up and through the snow, still coming down heavy. I could make out the shape of a large, bearded man in platelayer’s clothes.

“Tha must ha fallen onto th’ rail and knocked thisel eawt. Lucky aw were tekkin’ th’dog for a walk an’ saw thi. Let’s have a look at thi.”

I had a nasty bump on my head where I’d hit the rail and also felt as though I’d twisted my ankle when I went over.

“Con tha walk?” my rescuer asked.

“I’m not sure I can…but I have to relieve my mate in the box at 10.00.”

“Oh, he can wait a few minutes. Howd on to me an’ we’ll get you into my cabin just up th’line.”

We edged forward through the blizzard, both of us completely white, the snow biting into our faces like small sharp nails.

My rescuer pushed open the door of what looked like a platelayer’s cabin just set back from the track, I’d never seen it before. We entered a warm but dark room lit only by a blazing fire and an oil lamp on the table.

“Sit thiself on this chair,” he said. Let’s tek a look at thi. Wheer’s it hurtin’?

I explained about the bump to my head and what I thought was the sprained ankle from when I’d fallen.

“Let’s tek a look. Tha’s had a bit of bump awreet but it doesn’t look too bad. A sma’ cut but nowt much. We’ll soon fix that. Let’s have a look at that foot.”

He got on his knees in front of me and took hold of my injured left foot.

“Nowt to worry abeawt, but this meyt hurt for a minute lad.”

He got hold of my foot and gave it a good wrench. He was right, it was bloody painful.

“Ow! Bloody hell, what’re you doin’?” I asked.

“Don’t fratch, it’ll be awreet, tha’ll see. Now let’s get that head wound dressed.”

A bandage appeared from what looked like a battered old first aid box and he cut a couple of pieces, laying them on the table. He dabbed some sort of lotion on the bruise, had an odd smell that I can’t describe but quite pungent, then wrapped the bandage around my head, securing it with a knot.

“Tha’s had a nasty bang on th’yed, but tha’ll live. Aw’ve dabbed a bit o’comfrey on that bruise, it’ll heal it gradely weel in a day or two. Grew it in mi own garden. Let’s get thi up to th’box, tha should be fit for duty neaw.”

We went out into the cold night air to find the blizzard had stopped. The clouds had rolled away leaving a clear, starry night with the path up to the box illuminated by a full moon. About six inches of snow had fallen.

We walked in silence up towards the box, the lights getting closer and stronger as we trudged through the undisturbed snow. I held on to my rescuer and hopped along on one foot, not putting pressure on the injured one. The little dog ran by his side.

We got to the steps leading up to the box and I turned to wish my rescuer a hearty thanks, with an invitation to come up for a brew. I hadn’t even had chance to ask his name.

We got to the steps leading up to the box and I turned to wish my rescuer a hearty thanks, with an invitation to come up for a brew. I hadn’t even had chance to ask his name.

“Aw’ll tek me leave neaw, th’wife’s expectin’ me back. Aw think tha’ll find that yon foot is healed and just give that bruise on thi yead a couple o’days.”

I turned round and there was no sign of him.

But what was most strange was that there were no footprints leading away from the signalbox. Maybe the wind had blown some drifts across the path.

Before I had time to think any further, the signalbox door opened and Frank shouted down to me. “Are you alright Paul? Paddy had told me you were on your way and then that friggin’ blizzard came on. Worried you’d got caught out by that freight.”

“Well I’ve had a strange experience, that’s for sure. Is that kettle on?”

I entered the signalbox; inside it was pretty much the same as Entwistle, a standard L&Y design. The fire was blazing away merrily.

“What’s happened to thi lad? What’s the bandage for?” Frank asked.

I explained to him that I’d tripped on some lineside junk and fallen onto the track, knocking myself out. Someone had pulled me away just in time before the freight passed. Whoever it was, he’d saved my life. And on top of that he’d dressed my wound and my foot was no longer in pain. I realised I could walk on it as normal.

“Sounds like tha’s seen a boggart!” said Frank, a man well versed in Lancashire folklore and daft tales.

“Somebody helped me, that’s for sure. I owe my life to him, but I’ve not a clue who the bloody hell he was – and he just disappeared. A bit of blowing snow probably covered up his footprints but I’ve no idea where he went. He said he was out taking his dog for a walk.”

I described his appearance, as much as I could, to my colleague. Tall and thick set, beard. Wearing what looked like old-fashioned working clothes, railway greatcoat, smelling of tobacco. Spoke broad Lancashire.

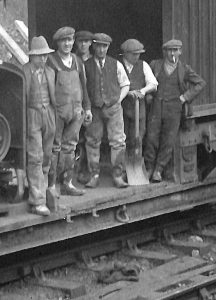

“Did he look like that chap, on the photograph over the frame?” Frank pointed to an old black and white photograph amongst a group of pictures of the line and the box, taken in the early 1900s by the look of them. Sure enough, one of the men in a group of platelayers was a spitting image, as much as I could see, of my rescuer. Even his clothes looked the same, with the cap and heavy overcoat. And there was the little dog by his side.

“That’s Bill Horrocks, he was foreman platelayer when there was still a small gang up here. Before the First World War. Bill was prominent in the railway first aid movement – chairman of the Bolton branch. He used to go round giving lectures on railway safety and first aid, won lots of prizes so they say. Swore by herbs, his house was full of all sorts of different lotions and potions. It’s ironic that he was killed in a railway accident, trying to rescue a workmate who’d fallen onto the rails, just down the line from here. He got his injured mate out of the way but didn’t have time to get out of the road himself. His little dog tried to pull him out of the way, so they say, but he was too heavy. Killed outright. They laid out his body in the old platelayer’s cabin just down the line – it’s derelict now, roof’s gone, but you can still see it from the line, if you look carefully. Anyway lad, I’ve arranged with the driver of the Newton Heath empties to give me a lift home and he’s just passed Spring Vale, so I’d better get down to meet him. Merry Christmas, and have an easy shift. Don’t see any more ghosts!”

Frank picked up his bag and disappeared down the steps. I saw the train’s lights as it emerged from Whittlestone Tunnel, slowing down to pick him up. A friendly toot on the horn and the train disappeared into the distance. I replaced my signals to danger and settled down to a quiet night, under the protective gaze of Bill Horrocks.

11 replies on “The First Aid Phantom of Wayoh Sidings”

Great story and love the reference to boggarts a much forgotten term and spirit these days

What a wonderful story, it’s made my day.

Great short story. Reminded me of back when I was a kid, growing up in Edgworth in the 60’s. We would spend hours trapping up and down the railway line. From Turton station over the Wayho viaduct through Entwistle Station and on throught what we local kids called the Suff tunnel, dangerous but as kids it was all just adventure to us.

Absolutely loved your ‘ tale ‘.

Thank You so much, would love to read more if you know any.

Merry Christmas.

Absolutely great read my father worked on the railways and I can remember going into a signal box and like in the story how warm it was reading your story brought it flooding back to me!! Fantastic story thank you for sharing it…

Thank you!

Loved the story Paul, especially the dialect references.

Seasonal greetings.

[…] The First Aid Phantom of Wayoh Sidings […]

What a fantastic story/experience… I’m a Horrocks, our family historically owned the quarry at Edgeworth and one of the sons, John, went on to start Horrocks textiles.

The dialect is spot on….

I found a link to this on a Facebook page about “time slips”, and read with interest as it was a local story, blew me away seeing Bills surname… If interested in whether Bill was an old relative of mine. Thanks for posting this, Paul.

Best regards

Lee Horrocks

Loved the story and the dialect especially made the character come alive.

Another great tale Paul …and to think it took place on the 23rd December..our wedding anniversary! Lots of boggarts in Ireland …x