Who Signed The Book?

A Christmas railway ghost story

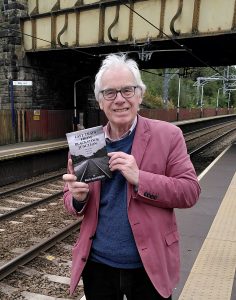

Paul Salveson

This was originally published in ASLEF’s Locomotive Journal in December 1985. This is a slightly updated version. Two years of my railway career were at at Astley Bridge Junction signalbox, Bolton, in the 1970s.

………………………………………………………………………

I’ve spent the last 40 years as union branch secretary getting other people out of trouble. I’ve done more disciplinaries than you’ll have had hot dinners – and I’ve had some bloody strange ones. But you want to know the strangest? I’ll tell you. It happened nearly 40 years ago and there’s enough water flown under the bridge for me to talk about it now. I’m long since retired so there’s not much anyone can do to me. I’ve got my pension.

I must have represented hundreds of my members at what they used to call ‘Form 1 hearings’. Disciplinaries. But this one found me in the hot seat. What led me to getting charged happened in 1983. Up to now the only people who knew anything about it are myself and Jack Bracewell, former Area Manager and he’s been retired even longer than me. He lives out Blackpool way. I promised I’d keep my mouth shut about the affair until Jack had finished and was getting his company pension. As a good union man, I’ve kept my word.

It was Christmas Eve 1983. I was working nights at Astley Bridge Junction; a small cabin just north of Bolton on the steeply-graded line to Blackburn. It’s long gone of course – shut when the branch to Halliwell Goods closed in the late 80s. It was the draughtiest box I’ve ever worked, stuck on top of Tonge Viaduct with only the birds and the circuit telephone to keep you company, apart from the occasional platelayer’s visit, usually Derek begging a brew of tea.

We’d had plenty of rows about it on the LDC – the old ‘Local Departmental Committee’ where we battled things out with management – usually good naturedly. Astley Bridge was one of the ancient Lancashire and Yorkshire (L&Y) boxes with facilities which could best be called ‘primitive’. Heating was by an old stove that  Stephenson probably invented, gas lighting and an outside toilet that froze every winter. And then that bloody draught that blew up from below, through the lever frame. Management kept telling us it was ‘in the programme’ for modernisation, but nothing happened.

Stephenson probably invented, gas lighting and an outside toilet that froze every winter. And then that bloody draught that blew up from below, through the lever frame. Management kept telling us it was ‘in the programme’ for modernisation, but nothing happened.

It had its compensations. You could look out across Bolton and see the dozens of mill chimneys, mostly still working then; turning north the moors stretched out before you. And it was cosy when you got the fire going, and no-one could say you were killed for work, with just a couple of trains each hour and the occasional goods on and off the branch. Years ago it had been on a through route to Scotland. Lancashire and Yorkshire expresses joined up with The Midland at Hellifield. Well before my time. Or so I thought.

At the time, we were working short-handed. My mate Joe Hepburn had retired three months previous and management were dragging their feet about filling the vacancy. So we were on regular twelve hours, George Ashcroft and myself. Good for the money, but not for your social life; nor, as I began to think, for your sanity.

Have you ever been to a Form 1 hearing? It’s probably different nowadays but back then it probably hadn’t changed since Victorian times. You sat there like a naughty schoolboy, usually accompanied by your union spokesman. If it was serious, the Area Manager would take the case and he’d read out the charge: “You are charged with the under-mentioned irregularity….etc.” A clerk would be sat in the background, taking notes of the ordeal and loving every minute of it, most times.

A good union man will use every argument in the book – and out of it – to get the poor bugger on the charge as good a deal as possible. I had a better success rate than many full-time union officers. I had just one rule: I never told a lie to get a member off the hook. If you pull that one, it might work the first time, but the boss would make it bloody hard for you the next. And that next time you might have had a genuine case.

So can you imagine how I felt, with 30 years’ service, including 20 as branch secretary, when I got that Form 1 addressed to me. But I’d been expecting it. And I thought I’d be the up the road.

The hearing was on a Friday morning in January 1984 at 09.00, in the Area Manager’s Office on Bolton station. Jack Bracewell, the AM, was an old hand whom I knew him from his days on the footplate. He was one of that dying breed of railway manager who’d started off at the bottom – as an engine cleaner at Plodder Lane shed – and worked his way up the ladder.

Ironically, I’d got him off the hook, years ago, by which time he’d got booked as a driver at Bolton. He was driving a loose-coupled coal train from Rose Grove to Salford Docks and I happened to be on duty at Astley Bridge Junction at the time, on relief. I got the’ train on line’ bell

from Bromley Cross box but I had an engine off the branch waiting at my starter to go back to the shed, so I couldn’t give the coal train a road. He’d have to wait at my home signal, just up from the end of the viaduct.

I heard a long piercing wheel then a series of short ‘crows’ – the steam whistle code for a runaway. I saw the train coming down the bank, with one of the old ‘Austerity’ locos, passing the home signal at danger. She was away, no doubt about it. Not going that fast but fast enough to give that light engine a nasty surprise if she caught up with it. Just as the loco passed the box I got ‘line clear’ from Bolton West and I quickly offered the light engine. It was accepted and I was able to clear my starter to get the light engine out of the way. The coal train shuddered to a halt just a few wagon lengths beyond my box.

The driver – Jack Bracewell – was quickly out of his cab and up the cabin steps. “Sorry mate – there was no holding her. Overloaded to start off with – we nearly stuck in Sough Tunnel – and that old wreck’s brake wouldn’t stop a push bike, ne’er mind 40 o’coal. Anyroad, put it in t’book and I’ll answer for passing that home board”.

Now some signalmen I knew would book a driver for not having his hair combed right, but I wasn’t going to get anyone into trouble if I could help it – even if he was an ASLEF man and I was NUR! “Didn’t you see?” I asked, “I pulled off for you to drop down to my starter just as you approached. Forget it.” We exchanged looks and Jack turned to leave. “Thanks mate – if you’re ever stuck, I’ll return the favour.”

I looked out of the cabin window and saw him climb back into the cab of his grimy ‘Austerity’, wheezing steam from everywhere but now looking calm and innocent after her wild descent from Walton’s Siding. I soon got ‘train out of section’ bell from Bolton West for the light engine and was able to pull off for Jack’s train. The wagons shuddered and screeched and he was back on his way to Salford Docks. The guard in the brake van looked a bit ashen-faced after his experience but I got a friendly and slightly relieved-looking wave from him.

That must have been….. what? 1959? Jack had come a long way since then, getting into management somewhere down south then promoted to Area Manager back in Bolton. Poacher turned gamekeeper we used to say. And the battles we had on the LDC! But at least you knew where you were with him. He was a railwayman and knew his job, and everyone else’s. That’s more than you can say for most of today’s management whizz-kids.

That day of the hearing I broke one of my golden rules. Never go into a disciplinary hearing without union representation. We’d fought hard for that right and many genuine cases were lost because someone thought they didn’t need any help. With me, it was more embarrassment than anything. I thought of asking Benny Jones the full-time officer, or some of my old mates on the NEC. But no, none of them would believe my story and I’d look a bloody fool. I went through that door on my tod, feeling very alone: one of the worst moments of my life.

Jack was at his desk, with the young woman clerk, Joyce Williams, sat at his side, pen in hand. She was one of the better ones, and I think she had a TSSA union card.

“Good morning Mr Hartshorn. Please sit down.” Jack was looking more bloody nervous than me. And Christ! I was a nervous wreck. He read the charge: ”You are charged with the under-mentioned irregularity. That on Wednesday December 24th 1983 you made incorrect entries in The Train Register Book, contrary to Signalmen’s Instructions and Rule Book Section such-and-such….What have you got to say in your defence?”

I looked across at Mr Jack Bracewell, Area Manager, BR London Midland Region. He’d put on weight since leaving the footplate; his face was a bright red and his hair receding. Maybe down to the hard time I’d given him at LDC meetings.

But today the advantage was firmly his – though you wouldn’t have thought so by the look of him. Beads of sweat rolled down his forehead, he shuffled uncomfortably in his chair. “Joyce” he blurted out…”turn that bloody heating down before we all roast.” The clerk jumped up and obeyed the command. The ball was now in my court.

“Before I give you my explanation Mr Bracewell I just want to remind you that I’ve always been straight when I’ve been representing my members in front of you. And I’m going to be straight with you now – however unbelievable it all might sound.”

“Of course…of course, get on with it.”

“Right. I relieved my mate at 6.00pm, as you know we were on 12 hours. I was sober, you can ask George to verify that if you want. We chatted for a few minutes about what we were doing over the holiday and then George signed off. “Could be a bad ‘un” I remember him saying about the weather; the snow had already started though lucky for him he didn’t live that far away. We wished each other ‘all the best’ and off he went down the cabin steps.

He’d left a good fire; the pot-bellied stove was glowing red. I settled myself down in the easy chair, with a quiet night’s work ahead of me. I saw the last ‘passenger’ through at 21.30h. It’s in the book. The only other scheduled train that night was the empty stock for Newton Heath at about 03.00. After it had gone I had permission to close the cabin early and not re-open until the following Monday, when I was early turn at 06.00.

I made a brew and settled down with my book – a thriller, funnily enough. To be honest I probably dozed off, at least for a few minutes. I was jolted out of my snooze by a ‘call attention’ bell from Bolton West. I wondered what on earth it could be. I looked at the clock and it showed 23.35. I gave the ‘1’ signal back to Bolton West and they offered me a ‘4’ – the bell code for an express passenger train, as you know, sir. The first thing that came into my mind was that the wires were down on the main line and Control was diverting some trains for Scotland via the Settle-Carlisle Line. It happens quite often, though it was very odd that I hadn’t got a circuit to tell me. Perhaps I’d been in more of a sleep than I thought and had missed the wire. I sent the signal on to Bromley Cross, got ‘line clear’ and pulled off – home board, starter and distant. Five minutes later I received a ‘2’ – train on line from Bolton West. I expected to hear the roar of a diesel engine, but instead I heard the steady, slow puff of a steam locomotive, obviously labouring on the gradient out of Bolton.

All I could think was that it must have been some sort of special working back to the museum at Carnforth, routed by Hellifield. It was a strange time to run it, but what was I to know? It was snowing very heavily by now, the wind blowing the flakes against the cabin windows so you could hardly see out. The tracks were completely covered.

The headlamps of the engine came into view; she’d slowed down even more and was barely moving though sparks were coming out of the chimney like a firework display.

“Aye the fireman would have the dart in to get the fire going,” said Jack reverting to his old footplate patter, quickly adding “but well, that’s if there was an engine…obviously. Delete that comment, Joyce.”

When the engine was almost level with the cabin the steam was shut off and the train came to a stand. I managed to open the cabin door, pushing the snow back, to get a better view.

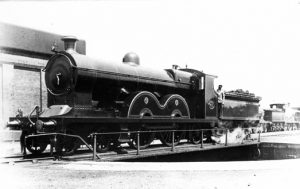

Through the blizzard I could see that it wasn’t one of the usual preserved locos you sometimes get – she looked older, but well kept. The paintwork looked jet black and across the tender I could make out the words ‘Lancashire & Yorkshire’.

She looked like one of those ‘Lanky’ Atlantics that some of the older signalmen used to talk about, when I was a train booker in my teens. ‘Highflyers’ they called them, with high-pitched long boilers. Very fast engines. But i couldn’t recall any being saved from the scrapheap.

The coaches looked vintage too, though i couldn’t see much of them through the snow. It was blowing like an arctic gale, and curious though I was, I had to shut the door.

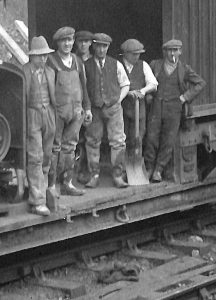

A moment later I heard footsteps coming up to the cabin. There was a rap on the door window. I took off the snack and opened the door to what looked like an oldish man – a gnarled face with a drooping moustache and eyes like red-hot coals. His hands were pitted and scarred. This didn’t look like some middle-class train enthusiast who did the occasional firing turn for the fun of it.

He walked in, shaking the snow off and carefully wiping his boots on the mat. “Short o’steam mate – they’re givin’ us rubbish t’burn wi’t’colliers on strike.”

By now I could get a proper look at him. He was dressed in old fashioned railway overalls which I’d only seen in history books. He had a very dignified appearance, reminding me of some of the old Methodist preachers I knew as a kid.

It was news to me that the miners were on strike, but that didn’t click at first. It took me a few seconds before I could say anything – though I offered him a brew and asked him to sign the Train Register Book, according to rule.

A few moments later more footsteps told me that his mate – the driver – was coming up for a warm as well. He looked about the same age as his fireman, slightly smaller with a long greying beard speckled with snowflakes and coal dust. He had similar overalls to his mate but wore a shirt and tie, with a shiny watch chain disappearing into his waistcoat pocket. He wore the L&Y insignia on his lapel. I remember thinking that if these two lads were steam buffs, they were certainly sticklers for historical accuracy.

The driver said, to no-one in particular, “There’ll be hell to play o’er this. Runnin’ short o’ steam on this job, we’st booath be on th’carpet o’Monday. It’s noan mi mates fault though – it’s that bad coyl they’re givin’ us. Tha cornt wark this sort o’job, wi’ nine bogies an just an hour to geet fro’ Bowton to Hellifield, wi nowt but th’best coyl. Th’bosses durnt give a bugger though – they just put th’blame on th’men.”

I didn’t know what to think. Was I caught up in an elaborate practical joke? Or was I in a time warp? I reminded myself that I hadn’t been drinking. Maybe I was still asleep and this was a very vivid dream. Yes – that was it. I’d soon wake up and get ‘call attention’ for the Newton Heath empties.

But it continued. The fireman went over to the stove to warn his pock-marked hands. “Th’company thinks as it con do what it wants wi’ us. It allus has done. But it’s geet a shock comin’. There’s talk o’one big union for all railwaymen after last year’s strike. Federation ‘ud be a good start. They’ve kept us divided for too long, grade agen grade, men agen men.”

The fireman halted for a while, feeling the heat return to his hands, and then continued “Aw’ve waited for th’day when we’d beat the company for a long time. Aw’ve suffered through bein’ a union man and socialist, like mony another. Moved fro’ shed t’ shed. Tret like dirt. Neaw there’s a change comin’.

The driver explained that his mate had been victimised following his part in the Wakefield strike…I’d never heard of it, even though I’d been a union man myself for 20-odd years. I had read about something kicking off around Wakefield in the union history, but that was way, way back. The bearded driver continued the story, explaining that the strike was broken by the company using fitters to drive the engines, with passenger guards providing the route knowledge. “Usual tale – divide an’ rule!” he added. The leaders were either sacked or transferred and told they’d be married to a shovel for the rest of their working lives.

His fireman finally ended up at Newton Heath shed, after several moves to holes like Bacup, Lees and Colne Lanky. He was still a fireman after 40 years service with no prospect of getting booked as a driver.

But hang on, was I playing a bit part in some union-sponsored costume drama? I could just remember reading about a big strike in 1911, before the NUR was formed. Were these blokes having me on?

“Aye,” said the driver. “There’ll be changes soon, reet enough. Anyroad, Aw’ll goo an’ oil reawnd. Valves are starting to pop so looks like we’ve got steam! Good night mate, and all the best.”

The fireman stayed a few moments longer and stood gazing round the cabin. “All reet these modern cabins, eh? Tha’s a bloody sight better off nor us locomen. Look what we’ve to put up wi’!” pointing outside to the snow-swept cab of his engine. “Still,” he continued, we know the long heawrs you lads have forced on you – sixteen hour days wi’ no overtime pay.” I thought of some of my mates, for whom the idea of working sixteen hours would be heaven – providing they got time and a half.

“Well brother. Aw’ll geet back – she’s blowin’ off neaw. She’ll get us up th’bank to Walton’s. Sooner we’re at Hellifield and relieved bi Midland men, the better. Hellifield lodging house allus does a gradely breakfast. Good neet and thanks for th’brew. Aw con tell a comrade when aw meet one.”

I watched him climb back onto the footplate and start shovelling more coal into the firebox. His mate stood by the long regulator handle, lit up by the glare from the fire. A shrill high-pitched whistle pierced the blizzard and the train began to move, with a powerful exhaust cutting through the snow storm.

I turned to my desk and looked at the Train Register Book. I noticed the fireman’s entry: “Detained within protection of signals. Rule 55.” The signature looked like ‘J.Weatherby’. If they were ghosts, they could sign their name!

I looked out of the cabin window and could just see the tail lamp in the distance. Suddenly it was gone, consumed by the blizzard. I gave a ‘2’ – train entering section – to Bromley Cross and sent the 2-1, train out of section, back to Bolton West. The entries are in the book and they were accurate to the minute. Both were recorded at 23.55.

The phone rang. It was Ernie Woodruff at Bolton West. “What’s that 2-1 tha just sent? Hasta gone daft?”

We nearly had a row. I told him he’d sent me a ‘4’ and the train had been detained at the box. I didn’t tell him what sort of train it was. Ernie denied sending the signal and said there’d been nothing on the block since the last passenger at 21.30. Anyway I thought, the proof would be when the train reaches Bromley Cross. That would show who’s daft, so I thought.

It never reached Bromley Cross. Ten minutes later, the signalman – Jack Seddon – rang to ask where this ‘4’ was. There was no sign of it on his track circuit. I told him he’d been having trouble and had maybe stuck again. It’s not unknown, even in the modern age, on that steeply-graded stretch of line.

We let another ten minutes pass and then decided something was up. As luck would have it, the Newton Heath empties were running early and were approaching Bromley Cross from Blackburn. Jack ‘put back’ his signals and cautioned the driver of the diesel train to inspect the line ahead. The train arrived at my box and the driver came into the box. He reported not having seen anything.

The driver – it was Jim Woods, an ex-Bolton man I’d know for years – asked how I was. I knew what was going through his mind, that I’d had a few Christmas Eve drinks too many before signing on. I said I was OK but I was anything but. At 01.00, as you’ll see in the book, I rang Control and asked for relief. I was no longer sure of my own sanity, and that’s the truth of it. I felt faint and disoriented. Jim made me a strong cup of tea and stayed with me until the block inspector, John Brooks, arrived to relieve me and close the box.

“You’ve heard the lot – make of it what you like Mr Bracewell.”

Jack sat back in his chair – so far he nearly overbalanced. It was a few seconds before he spoke…it seemed like a very long time.

“Joyce, love, go and make us a cup of tea will you. And one for Mr Hartshorn.”

The clerk got up and left the room, leaving us alone. “Right John. This is off the record, just thee an’ me. You’d had a few, right? It was Christmas. Just tell me the truth. I owe you a favour, we’ll get round this somehow. Listen, if anybody else had told me that load of bollocks I’d have had ‘em cleaning out the carriage shed shit house before they could say boo to a bleedin’ goose. Now come on.”

“I’m sorry Jack, I don’t expect you, nor anyone else, to believe it. I wouldn’t myself if someone else I’d been representing had told me all that.

Bracewell was quiet for several minutes. This was the man I knew. Working out a plan, weighing up the options.

“Look, he said at last. “I’ll tell you what. You’d been under strain with all those 12 hour shifts. You’d had a lot of union work on too. Maybe you’d had a few pints before coming on duty and you fell asleep. You’re brain wandered.”

“Sure Jack. But how can anyone explain the entry in the Train Register Book?”

“Easy. We’ll just say you’d been dreaming and….err….” he dried up.

“Who was it that signed the book Jack? That’s not my signature. It looks like ‘J. Weatherby’. Who was this character that signed the book?”

“Who signed the book….who….” he mumbled and went quiet.

He came up with another ‘solution’. “I know. There’s a platelayer called ‘Weatherall’ isn’t there?”

“Aye, I responded. Dave Johnny Weatherall. He was on snow duty at Bolton East that night as it happens but didn’t came anywhere near Astley Bridge.”

“Never mind that. We can say he came up to check the points and made a balls-up of the entry in to the Train Register Book.”

“Listen Jack. I’m not getting anyone else into bother over this. It’s my problem, no-one else’s.”

“Look you awkward bugger. I owe you a good turn. And I’m going to do you one if I have to get paid up for doing it. Nothing ‘ll happen to Weatherall, I’ll see to that. Trust me.”

I did. I went along with his tale. I got off with a reprimand; I was lucky. Extremely lucky. If it had been that young Assistant AM – fresh out of college – taking the case it might have been dismissal. But it didn’t solve the problem for me. What had happened that night? Had I temporarily gone mad? I could never really trust myself handling traffic again until I was sure, one way or the other.

I took a few days leave that were due to me and then resumed at Astley Bridge Junction. I was on days – we were back to 8 hour shifts. On the first day a group of workmen arrived.

“You’re in luck mate!” the foreman beamed. “You’re getting them mod-cons you’ve been after all these years”. The gang set to work taking out the old fittings, removing the old stove and putting in a gas heater, new toilet, modern block equipment and even new lino for the floor.

It wasn’t until the following day they started work on the last job, stripping out the old linoleum floor covering, that had been polished zealously by generations of signalmen. It was a messy and disruptive job getting it out.

I was trying to complete a member’s accident claim for head office when one of the lads piped up: “Hey, look at these old newspapers stuffed under the lino. Bet they’re worth a bob or two!”

I went over and picked one of them up. The paper was perished and discoloured. But I could read it well enough. It was the front page of The Bolton Evening News for December 26th, 1912.

“TERRIBLE CHRISTMAS EVE TRAGEDY – EXPRESS CRASHES OVER VIADUCT IN BLIZZARD. MANY KILLED”

I read on. The train was a Scotch extra for the Christmas holidays, routed via Settle. The viaduct had collapsed at about midnight and the train careered into the river below. There was a list of casualties who had been identified so far. The catalogue of men, women and several children made tragic reading.

At the end of the list was “Mr James Weatherby, the fireman of the locomotive”.

only way you could reach it was by walking up the line from Entwistle, just over a mile. There was no road access and the other relief men didn’t like it – they couldn’t get there by car. I was young and fit back then and would either walk or even cycle up the path along the line, keeping an eye out for passing trains. If it was wet, most drivers – if you asked them nicely – would drop you off outside the box.

only way you could reach it was by walking up the line from Entwistle, just over a mile. There was no road access and the other relief men didn’t like it – they couldn’t get there by car. I was young and fit back then and would either walk or even cycle up the path along the line, keeping an eye out for passing trains. If it was wet, most drivers – if you asked them nicely – would drop you off outside the box. drift back to base. If there was nothing else about, the driver and fireman would park their engine outside and come up for a brew.

drift back to base. If there was nothing else about, the driver and fireman would park their engine outside and come up for a brew. Entwistle and Wayoh, provided by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to give extra capacity for freight trains. By the 60s there wasn’t much freight, apart from the evening Burnley – Moston on the up line and the Ancoats – Carlisle on the down.

Entwistle and Wayoh, provided by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to give extra capacity for freight trains. By the 60s there wasn’t much freight, apart from the evening Burnley – Moston on the up line and the Ancoats – Carlisle on the down.

walking into the wind, howling down from Whittlestone Head and blowing the snow horizontally. I was struggling to see and the snow felt more like small balls of ice.

walking into the wind, howling down from Whittlestone Head and blowing the snow horizontally. I was struggling to see and the snow felt more like small balls of ice. We got to the steps leading up to the box and I turned to wish my rescuer a hearty thanks, with an invitation to come up for a brew. I hadn’t even had chance to ask his name.

We got to the steps leading up to the box and I turned to wish my rescuer a hearty thanks, with an invitation to come up for a brew. I hadn’t even had chance to ask his name.

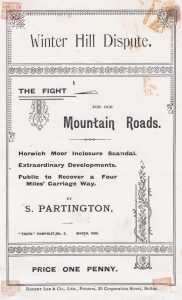

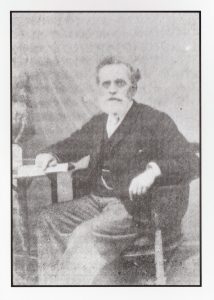

cause with local socialists such as Joseph Shufflebotham in organising opposition to Ainsworth’s footpath closure, and a demonstration was organised for Sunday September 6th 1896, with announcements in the Bolton Journal and Guardian and other local papers that it would set off at 10.00 from the Bottom of Halliwell Road, ‘to test the right of way’. A few hundred gathered at the start of the march, but by the time it reached The Ainsworth Arms, at the top of Halliwell Road, the ranks had swelled to about 10,000. There was a melee at the point where Ainsworth ahd erected a gate to deter walkers, and the gate was unceremoniously destroyed. Further demonstrations followed, with the following Sunday’s being the biggest, with an estimated 12,000 taking part. Partington’s experience with the ‘Thousand Lads’ march in Leigh, over ten years previously, was clearly being put to good effect.

cause with local socialists such as Joseph Shufflebotham in organising opposition to Ainsworth’s footpath closure, and a demonstration was organised for Sunday September 6th 1896, with announcements in the Bolton Journal and Guardian and other local papers that it would set off at 10.00 from the Bottom of Halliwell Road, ‘to test the right of way’. A few hundred gathered at the start of the march, but by the time it reached The Ainsworth Arms, at the top of Halliwell Road, the ranks had swelled to about 10,000. There was a melee at the point where Ainsworth ahd erected a gate to deter walkers, and the gate was unceremoniously destroyed. Further demonstrations followed, with the following Sunday’s being the biggest, with an estimated 12,000 taking part. Partington’s experience with the ‘Thousand Lads’ march in Leigh, over ten years previously, was clearly being put to good effect. totalling £565 were awarded against the protestors and Partington and his friend (and treasurer of the Defence Committee) William Hutchinson found themselves saddled with having to find £600. His erstwhile socialist friends appeared to have abandoned them. Partington mounted an energetic campaign to recover some of the costs; the most generous supporter was William Hesketh Lever (Later Lord Levehulme) who contributed £100. A further £165 was given by local people including the Liberal M.P. George Harwood.

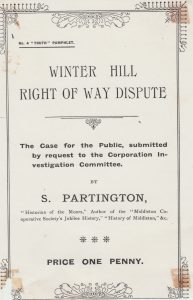

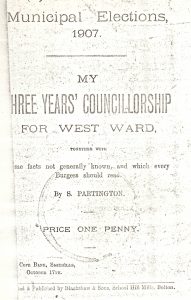

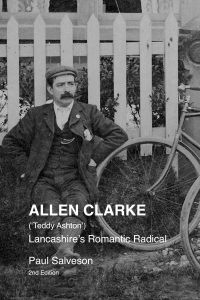

totalling £565 were awarded against the protestors and Partington and his friend (and treasurer of the Defence Committee) William Hutchinson found themselves saddled with having to find £600. His erstwhile socialist friends appeared to have abandoned them. Partington mounted an energetic campaign to recover some of the costs; the most generous supporter was William Hesketh Lever (Later Lord Levehulme) who contributed £100. A further £165 was given by local people including the Liberal M.P. George Harwood. seems he became frustrated with the lack of support for his campaigns within the local Liberal Party and became more aligned to the local Labour Party. His election agent was Allen Clarke who used the pages of his Teddy Ashton’s Northern Weekly to win support for Partington.

seems he became frustrated with the lack of support for his campaigns within the local Liberal Party and became more aligned to the local Labour Party. His election agent was Allen Clarke who used the pages of his Teddy Ashton’s Northern Weekly to win support for Partington. operative Society was published in 1920. Partington remained in touch with public rights of way campaigners in Bolton and wrote an extended letter to Bolton Housing and Town Planning Committee in 1915, highlighting unresolved footpath issues.

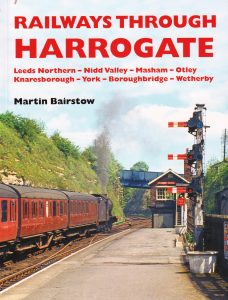

operative Society was published in 1920. Partington remained in touch with public rights of way campaigners in Bolton and wrote an extended letter to Bolton Housing and Town Planning Committee in 1915, highlighting unresolved footpath issues. close lines which, had they survived, would have been thriving and part of the electrified network, for certain. There is a fascinating chapter on accidents and the railways’ sometimes reluctant efforts to make their operations safer. The chapter titled ‘Lock, Block and Brake’ pus railway safety in a wider political context, making use of Bairstow’s encyclopedic parliamentary knowledge. There’s an interesting section on the Poppleton Community Railway Nursery, just outside York. I was about to say that there can’t be many garden centres with their own railway but actually there’s quite a few. Poppleton’s claim to fame is that it was an original railway nursery, created by the LNER during the Second World War, and was the very last. I gave a helping hand in rescuing the nursery in my Northern Rail days and it now thrives as a community project.

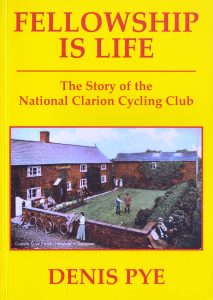

close lines which, had they survived, would have been thriving and part of the electrified network, for certain. There is a fascinating chapter on accidents and the railways’ sometimes reluctant efforts to make their operations safer. The chapter titled ‘Lock, Block and Brake’ pus railway safety in a wider political context, making use of Bairstow’s encyclopedic parliamentary knowledge. There’s an interesting section on the Poppleton Community Railway Nursery, just outside York. I was about to say that there can’t be many garden centres with their own railway but actually there’s quite a few. Poppleton’s claim to fame is that it was an original railway nursery, created by the LNER during the Second World War, and was the very last. I gave a helping hand in rescuing the nursery in my Northern Rail days and it now thrives as a community project. close links with the Independent Labour Party and a plethora of local socialist organizations. In parts of Lancashire and Yorkshire members created ‘Clarion club houses’ which acted as workers’ holiday resorts – you could call in for lunch during a ride, or you could stay for a few weeks and enjoy a game of tennis, read uplifting books and argue socialism, anarchism and liberalism with fellow guests. One survives, the Clarion House at Roughlee, near Nelson. It was visited by Michael Portillo in his ‘Great Railway Journeys’ and in true Lancashire socialist style he was given a warm, friendly welcome.

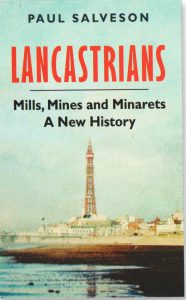

close links with the Independent Labour Party and a plethora of local socialist organizations. In parts of Lancashire and Yorkshire members created ‘Clarion club houses’ which acted as workers’ holiday resorts – you could call in for lunch during a ride, or you could stay for a few weeks and enjoy a game of tennis, read uplifting books and argue socialism, anarchism and liberalism with fellow guests. One survives, the Clarion House at Roughlee, near Nelson. It was visited by Michael Portillo in his ‘Great Railway Journeys’ and in true Lancashire socialist style he was given a warm, friendly welcome. and literature. Lancashire developed a distinct business culture, its shrine being the Manchester Cotton Exchange, but this was also the birthplace of the world co-operative movement, and the heart of campaigns for democracy including Chartism and women’s suffrage. Lancashire has generally welcomed incomers, who have long helped to inform its distinctive identity: fourteenth-century Flemish weavers; nineteenth-century Irish immigrants and Jewish refugees; and, more recently, New Lancastrians from Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. The book explores what has become of Lancastrian culture, following modern upheavals and Lancashire’s fragmentation compared with its old rival Yorkshire. What is the future for the 6 million people of this rich historic region?”

and literature. Lancashire developed a distinct business culture, its shrine being the Manchester Cotton Exchange, but this was also the birthplace of the world co-operative movement, and the heart of campaigns for democracy including Chartism and women’s suffrage. Lancashire has generally welcomed incomers, who have long helped to inform its distinctive identity: fourteenth-century Flemish weavers; nineteenth-century Irish immigrants and Jewish refugees; and, more recently, New Lancastrians from Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. The book explores what has become of Lancastrian culture, following modern upheavals and Lancashire’s fragmentation compared with its old rival Yorkshire. What is the future for the 6 million people of this rich historic region?”

The socialist writer Allen Clarke was one of the foremost proponents of a Lancashire sensibility, through his stories, poems and songs. Many Conservative figures such as the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres were proud of their Lancashire roots and supported bodies which promoted Lancashire culture.

The socialist writer Allen Clarke was one of the foremost proponents of a Lancashire sensibility, through his stories, poems and songs. Many Conservative figures such as the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres were proud of their Lancashire roots and supported bodies which promoted Lancashire culture.

starting to change. One note of caution: not everyone, whatever their ethnicity, actually likes the idea of going for a walk in the country and that’s their prerogative. But it’s clear that people from BAME communities are disproportionately under-represented amongst country walkers and that needs thinking about. Personally I’m not too keen on the concept of ‘safe spaces’ where people retreat into a cocoon against a real or imagined ‘threat’. And there’s a risk we manufacture a fear that walking in the outdoors is somehow dangerous and threatening. It isn’t. It’s a lot safer than walking down Bradshagate on a Friday night.

starting to change. One note of caution: not everyone, whatever their ethnicity, actually likes the idea of going for a walk in the country and that’s their prerogative. But it’s clear that people from BAME communities are disproportionately under-represented amongst country walkers and that needs thinking about. Personally I’m not too keen on the concept of ‘safe spaces’ where people retreat into a cocoon against a real or imagined ‘threat’. And there’s a risk we manufacture a fear that walking in the outdoors is somehow dangerous and threatening. It isn’t. It’s a lot safer than walking down Bradshagate on a Friday night. a distinct county stretching from the Mersey to the Lake District—‘Lancashire North of the Sands’. From a relatively backward place in terms of industry and learning, Lancashire would become the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution: the creation of a self-confident bourgeoisie drove economic growth, and industrialists had a strong commitment to the arts, endowing galleries and museums and producing a diverse culture encompassing science, technology, music and literature. Lancashire developed a distinct business culture, its shrine being the Manchester Cotton Exchange, but this was also the birthplace of the world co-operative movement, and the heart of campaigns for democracy including Chartism and women’s suffrage. Lancashire has generally welcomed incomers, who have long helped to inform its distinctive identity: fourteenth-century Flemish weavers; nineteenth-century Irish immigrants and Jewish refugees; and, more recently, New Lancastrians from Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. The book explores what has become of Lancastrian culture, following modern upheavals and Lancashire’s fragmentation compared with its old rival Yorkshire. What is the future for the 6 million people of this rich historic region?”

a distinct county stretching from the Mersey to the Lake District—‘Lancashire North of the Sands’. From a relatively backward place in terms of industry and learning, Lancashire would become the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution: the creation of a self-confident bourgeoisie drove economic growth, and industrialists had a strong commitment to the arts, endowing galleries and museums and producing a diverse culture encompassing science, technology, music and literature. Lancashire developed a distinct business culture, its shrine being the Manchester Cotton Exchange, but this was also the birthplace of the world co-operative movement, and the heart of campaigns for democracy including Chartism and women’s suffrage. Lancashire has generally welcomed incomers, who have long helped to inform its distinctive identity: fourteenth-century Flemish weavers; nineteenth-century Irish immigrants and Jewish refugees; and, more recently, New Lancastrians from Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. The book explores what has become of Lancastrian culture, following modern upheavals and Lancashire’s fragmentation compared with its old rival Yorkshire. What is the future for the 6 million people of this rich historic region?”

music venue which, obviously, does real ale. Go back down Bridge Street to The Circus, the epi-centre of Darwen and a place of many exciting performances over the years. Across the road are two very pretty domed buildings which were once connected to Darwen Corporation’s tram system – welcome correction here but I think one was a waiting room and the other was a ticket office. Just across from there is the site of the former wallpaper and paint works which Darwen became synonymous with. Instead of heading up Bolton Rod, I went up the hill towards Bold Ventre Park, through some very attractive stone terraced streets. The park is one of Darwen’s three gems, the

music venue which, obviously, does real ale. Go back down Bridge Street to The Circus, the epi-centre of Darwen and a place of many exciting performances over the years. Across the road are two very pretty domed buildings which were once connected to Darwen Corporation’s tram system – welcome correction here but I think one was a waiting room and the other was a ticket office. Just across from there is the site of the former wallpaper and paint works which Darwen became synonymous with. Instead of heading up Bolton Rod, I went up the hill towards Bold Ventre Park, through some very attractive stone terraced streets. The park is one of Darwen’s three gems, the

Eccles Shorrock and fully opened in 1871. Mr Shorrock was clearly fond of ‘big statements’ and supposedly invited some of his workers to a gala dinner on the top of the chimney when the job was finished. Definitely an unmissable event if you were lucky enough to be on the invitation list. However, there is some doubt whether the dinner was fact or fiction. Alan Duckworth, who has written an excellent novel which features the mill, said: “What about the dinner held on top of the chimney when it was completed? It is further said that a band played up there while they ate. Certainly there was a dinner held at ground level in the Crown Inn on December 12th 1868 for the 52 men responsible for building the chimney, but had they earlier dined at the top of the chimney? It’s a good story and deserves to be true and the men must have eaten their meals up there when they were working on it, but there’s a difference between a bacon buttie gulped down in the teeth of the wind and a sit down meal with table linen and a band accompaniment.”

Eccles Shorrock and fully opened in 1871. Mr Shorrock was clearly fond of ‘big statements’ and supposedly invited some of his workers to a gala dinner on the top of the chimney when the job was finished. Definitely an unmissable event if you were lucky enough to be on the invitation list. However, there is some doubt whether the dinner was fact or fiction. Alan Duckworth, who has written an excellent novel which features the mill, said: “What about the dinner held on top of the chimney when it was completed? It is further said that a band played up there while they ate. Certainly there was a dinner held at ground level in the Crown Inn on December 12th 1868 for the 52 men responsible for building the chimney, but had they earlier dined at the top of the chimney? It’s a good story and deserves to be true and the men must have eaten their meals up there when they were working on it, but there’s a difference between a bacon buttie gulped down in the teeth of the wind and a sit down meal with table linen and a band accompaniment.”

superb and I very much hope whatever becomes of the pub its heritage features will be protected.

superb and I very much hope whatever becomes of the pub its heritage features will be protected.

(Bolton – Bury – Rochdale) and the 163 (Bury – Middleton – Manchester). But how I miss the train that ran from Rochdale via Heywood, Bury and Radcliffe to Bolton. You can still get steam haulage on the East Lancs, and who would have thought in 2022 you’d be able to travel behind a Southern Pacific or an LNER A4 from Heywood to Bury?

(Bolton – Bury – Rochdale) and the 163 (Bury – Middleton – Manchester). But how I miss the train that ran from Rochdale via Heywood, Bury and Radcliffe to Bolton. You can still get steam haulage on the East Lancs, and who would have thought in 2022 you’d be able to travel behind a Southern Pacific or an LNER A4 from Heywood to Bury?

After the attack by metal thieves the railway’s appeal has proved successful and the track is gradually being re-laid. Not quite there yet but the railway is able to operate an ‘out and back’ service, for donations.

After the attack by metal thieves the railway’s appeal has proved successful and the track is gradually being re-laid. Not quite there yet but the railway is able to operate an ‘out and back’ service, for donations.

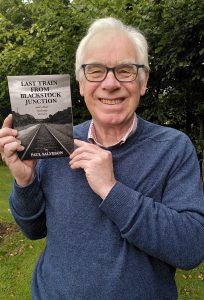

Director of Platform 5 Publishing, Andrew Dyson, said “Paul’s stories provide a fascinating insight into what life was really like for thousands of railway workers.”

Director of Platform 5 Publishing, Andrew Dyson, said “Paul’s stories provide a fascinating insight into what life was really like for thousands of railway workers.”

Bacup Line which closed to passengers in 1947 and to freight in 1967 (though the line beyond Whitworth had shut completely in 1963). The Locomotive Club of Great Britain ran a special train in April 1967 comprising four guards’ brake vans hauled by L&Y ‘Pug’ 51218 – which is still very much alive and well.

Bacup Line which closed to passengers in 1947 and to freight in 1967 (though the line beyond Whitworth had shut completely in 1963). The Locomotive Club of Great Britain ran a special train in April 1967 comprising four guards’ brake vans hauled by L&Y ‘Pug’ 51218 – which is still very much alive and well.

Our ‘golden age’ was the time of post-war Austerity and the Labour Government of Clem Attlee. It was a highly statist politics, which was probably what was needed to recover from the horrors and destruction of the Second World War. Yet there are quite a few who still think that political and economic model is what the country needs today. You can summarise it as ‘Corbynism’. A pity he didn’t listen more to his pal John McDonnell who did have some good, radical, ideas on the economy.

Our ‘golden age’ was the time of post-war Austerity and the Labour Government of Clem Attlee. It was a highly statist politics, which was probably what was needed to recover from the horrors and destruction of the Second World War. Yet there are quite a few who still think that political and economic model is what the country needs today. You can summarise it as ‘Corbynism’. A pity he didn’t listen more to his pal John McDonnell who did have some good, radical, ideas on the economy. onto the 582 Leigh bus at Bolton Interchange and headed through Atherton and past the superb miners’ cottages at Howe Bridge, built as showpieces by the Fletcher Burrows company. If only all miners’ housing had been built like that. All was going well until we reached the edge of the town centre, with ‘diversion’ signs directing us onto a convoluted route round the back of town. Yes, I know, I should have got off when the diversion started but stayed on, for another 20 minutes as it turned out. The diversion was on account of various festivities taking place around the 2022 European Women’s Football Championship, some matches being played in Leigh (I think England v Portugal). A ‘fan party’ was taking places in the Market Square, hence the diversions (actually, I’m not really sure why they had to close the road, but anyway…).Leigh Archives are located in the town hall which was in the ‘secure area’ where the fan party was taking place, so I dutifully showed the security staff the contents of my bag (flask, cheese sandwich, wagon wheel and note book) and was allowed in. The archives weren’t open because of all the other goings-on but I had a good look round the local history museum, which is excellent. Two of my favourite ‘Leythers’, Tom Burke and Mary Thomason, were prominently featured. You could press a button and hear Tom singing one of his arias, and another to listen to Mary reciting a dialect poem. The effect of pushing both at once, as some children insisted in doing, was slightly odd (it was a day of odd, but enjoyable, things) but nice all the same to hear Tom Burke singing, in Leigh. Part of my quest in going to the Leigh Archives was to look at copies of The Leigh Co-operative Record, which Mary wrote for in the 1920s.

onto the 582 Leigh bus at Bolton Interchange and headed through Atherton and past the superb miners’ cottages at Howe Bridge, built as showpieces by the Fletcher Burrows company. If only all miners’ housing had been built like that. All was going well until we reached the edge of the town centre, with ‘diversion’ signs directing us onto a convoluted route round the back of town. Yes, I know, I should have got off when the diversion started but stayed on, for another 20 minutes as it turned out. The diversion was on account of various festivities taking place around the 2022 European Women’s Football Championship, some matches being played in Leigh (I think England v Portugal). A ‘fan party’ was taking places in the Market Square, hence the diversions (actually, I’m not really sure why they had to close the road, but anyway…).Leigh Archives are located in the town hall which was in the ‘secure area’ where the fan party was taking place, so I dutifully showed the security staff the contents of my bag (flask, cheese sandwich, wagon wheel and note book) and was allowed in. The archives weren’t open because of all the other goings-on but I had a good look round the local history museum, which is excellent. Two of my favourite ‘Leythers’, Tom Burke and Mary Thomason, were prominently featured. You could press a button and hear Tom singing one of his arias, and another to listen to Mary reciting a dialect poem. The effect of pushing both at once, as some children insisted in doing, was slightly odd (it was a day of odd, but enjoyable, things) but nice all the same to hear Tom Burke singing, in Leigh. Part of my quest in going to the Leigh Archives was to look at copies of The Leigh Co-operative Record, which Mary wrote for in the 1920s. across the square, so I thought I’d pop across and see what was going on, before heading back to Bolton. There was a bit of a commotion going on in the library foyer but I was told I’d be OK to squeeze through the assembled throng. The said throng comprised a large number of young Asian lads dressed in regimental Highland costume, wielding an assortment of pipes and drums. It was the Shree Muktajeevan Swamibapa Pipe Band, all the way from Bolton. They made an impressive sight as they emerged from the Library foyer to perform around the Market Place, and an even more impressive sound. The band uniform includes a black bonnet with white and red feather, black doublet, blue tartan kilt, sporran, and a blue tartan plaid. Some of the members were young lads, clearly enjoying themselves, as were the spectators. The whole scene was made even more surreal (difficult, I know) by the two giant fairies who were swirling around to the music. After the performance was over I had a look at the open-air exhibition on women’s football. It’s not a sport I’ve had much interest in but the exhibition highlighted interesting aspects of local women’s football, including their fundraising efforts during the 1921 Miners’ Lockout. So the there you are, learn summat new every day, eh?

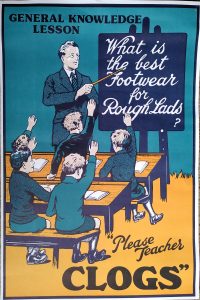

across the square, so I thought I’d pop across and see what was going on, before heading back to Bolton. There was a bit of a commotion going on in the library foyer but I was told I’d be OK to squeeze through the assembled throng. The said throng comprised a large number of young Asian lads dressed in regimental Highland costume, wielding an assortment of pipes and drums. It was the Shree Muktajeevan Swamibapa Pipe Band, all the way from Bolton. They made an impressive sight as they emerged from the Library foyer to perform around the Market Place, and an even more impressive sound. The band uniform includes a black bonnet with white and red feather, black doublet, blue tartan kilt, sporran, and a blue tartan plaid. Some of the members were young lads, clearly enjoying themselves, as were the spectators. The whole scene was made even more surreal (difficult, I know) by the two giant fairies who were swirling around to the music. After the performance was over I had a look at the open-air exhibition on women’s football. It’s not a sport I’ve had much interest in but the exhibition highlighted interesting aspects of local women’s football, including their fundraising efforts during the 1921 Miners’ Lockout. So the there you are, learn summat new every day, eh? which I’ve yet to use, but will do, soon. That was Clog Experience Pt. 1. The next was a visit to Mytholmroyd, mainly to see Sue and Geoff Mitchell with new CRP Officer Karen. We inspected the work going on to bring the historic station building back to life, and then – special treat – a visit to Walkley’s Clogs. What a delightful treat. Very friendly people, Sue and Alan are clearly clog cranks par excellence and delighted showing me round the shop.

which I’ve yet to use, but will do, soon. That was Clog Experience Pt. 1. The next was a visit to Mytholmroyd, mainly to see Sue and Geoff Mitchell with new CRP Officer Karen. We inspected the work going on to bring the historic station building back to life, and then – special treat – a visit to Walkley’s Clogs. What a delightful treat. Very friendly people, Sue and Alan are clearly clog cranks par excellence and delighted showing me round the shop. My mother and her friends always wore headscarves when they went out and in the mill wore them as ‘turbans’ to protect their hair from the grease and dangerous machinery. Indoors they always wore wrap-around pinnies, (aprons) with pockets, to keep their clothes clean. This was in the days before washing machines when clothes were scrubbed on a washboard, rinsed in the sink and put through the mangle before being pegged on the line or hung on the hoisted dryer which hung near the fireplace.”

My mother and her friends always wore headscarves when they went out and in the mill wore them as ‘turbans’ to protect their hair from the grease and dangerous machinery. Indoors they always wore wrap-around pinnies, (aprons) with pockets, to keep their clothes clean. This was in the days before washing machines when clothes were scrubbed on a washboard, rinsed in the sink and put through the mangle before being pegged on the line or hung on the hoisted dryer which hung near the fireplace.” his tools are in York museum. They were given to me on my first birthday and I still cherish them. I wore clogs up to first year in high school but they got banned after sliding a cross the parquet floor in the hall (irons)! My current ones are ‘Sunday Best’ made by Walkleys, which I use for dancing in regularly these days. They’re shod with homemade stainless irons for longevity.”

his tools are in York museum. They were given to me on my first birthday and I still cherish them. I wore clogs up to first year in high school but they got banned after sliding a cross the parquet floor in the hall (irons)! My current ones are ‘Sunday Best’ made by Walkleys, which I use for dancing in regularly these days. They’re shod with homemade stainless irons for longevity.” Clogs were worn by the workers in the cotton mills to keep their feet warm and dry. Here comes the interesting part! To alleviate boredom and to warm up, the workers started “Clog Dancing” which involved heavy steps which kept time (clog is Gaelic for ‘time’), and along with striking one shoe with the other, created rhythms and sounds to imitate those made by the milling machinery! Clog Dancing originated as a way of relieving the monotonous labour and physical repetition without being overpowered by the industrial machine.”

Clogs were worn by the workers in the cotton mills to keep their feet warm and dry. Here comes the interesting part! To alleviate boredom and to warm up, the workers started “Clog Dancing” which involved heavy steps which kept time (clog is Gaelic for ‘time’), and along with striking one shoe with the other, created rhythms and sounds to imitate those made by the milling machinery! Clog Dancing originated as a way of relieving the monotonous labour and physical repetition without being overpowered by the industrial machine.”