THE LANCASHIRE LOOMINARY

An occasional update from Lancashire Loominary

No. 7 December 2021

Welcome to the December edition of Lancashire Loominary, an occasional update for readers and friends of Lancashire Loominary publications. It’s probably not too early to wish you a very happy Christmas. If you have bought any of my books over the last year, a particular thanks. It hasn’t been an easy time to be a small publisher (but when is?). Next year I’m hoping to bring out a new book on the history, present state and possible future of ‘Greater Lancashire’ as well as a collection of my local history features from The Bolton News, if they don’t mind, to be called Our Bolton.

This edition features an extended version of my article on Victor Grayson – the socialist MP who disappeared, almost without trace, after the First World War. His links to Bolton are highlighted, with scope for a bit more digging. There is a print version (a bit shorter but with pictures) in the current Big Issue North – which also carries a good piece by Chris Moss on Northern regionalism and the Hannah Mitchell Foundation (which is holding a conference on ‘Real Levelling Up’ on Saturday December 4th (www.hannah-mitchell.org.uk for details). Please buy BIN if you get the opportunity.

There’s what I hope is an attractive ‘readers’ offer’ for my books – see below. I also have a bit to say about HS2 and its partial cancellation. As usual, I don’t go with the tide!

Readers’ offers for Christmas

I currently have four books in stock – the full cover price is shown in brackets and details of the very generous (!) reductions for Loominary readers are given at the end of this newsletter:

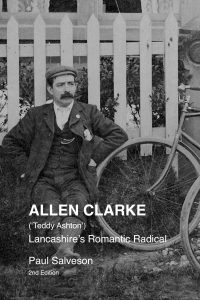

- Allen Clarke (‘Teddy Ashton’) Lancashire’s Romantic Radical ( £18.99)

- Moorlands, Memories and Reflections (£21)

- The Works (a novel set in Horwich Loco Works £12.99

- With Walt Whitman in Bolton: spirituality, sex and socialism in a Northern Milltown (£8.99)

Some of these, as you’ll see from my website, are already available direct from me at a discounted price. Up to the end of the year I’m doing some further special offers which include:

- Buy one get one free (the lowest priced one)

- ‘two for price of one’ for same title

- Bundle of all four titles for £30 (plus postage if not local)

Feature article: the mysterious Victor Grayson

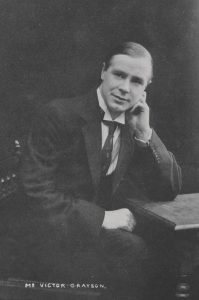

A young socialist firebrand called Victor Grayson shot to international fame in 1907 by winning a by-election in the Yorkshire textile constituency of Colne Valley, on an uncompromising left wing programme.  He was defeated in 1910 and ten years later vanished, almost without trace. The story of his meteoric rise, and subsequent disappearance, is a fascinating chapter in British political history, very ably explored by the work of historians David Clark and more recently Harry Taylor whose biography Victor Grayson: in search of Britain’s lost revolutionary, was published recently. Bolton features prominently in the story of his life and subsequent disappearance.

He was defeated in 1910 and ten years later vanished, almost without trace. The story of his meteoric rise, and subsequent disappearance, is a fascinating chapter in British political history, very ably explored by the work of historians David Clark and more recently Harry Taylor whose biography Victor Grayson: in search of Britain’s lost revolutionary, was published recently. Bolton features prominently in the story of his life and subsequent disappearance.

Early years

Grayson was born in the Scotland Road district of Liverpool, of working class parents, in 1881 – though even this fact has been questioned, as we shall see. He had an adventurous boyhood, leaving home at the age of 14 to see the world, as a stowaway on board a ship bound for Chile – though he only got as far as Tenby, after being discovered.

Not much is known of his teenage years. He was an intelligent and resourceful lad with a strong social conscience and was apprenticed in an engineering works. He experienced poverty at first hand in the Liverpool slums and wanted to do something about it. In 1904 he enrolled as a student at the Unitarian college in Manchester to train as a minister; however he became increasingly involved in the socialist movement which was sweeping the North of England, inspired by the Clarion newspaper, edited by Robert Blatchford who was to become a close friend.

A popular socialist orator

By the following year, Grayson had become a popular figure on the socialist lecturing circuit across the North of England. He was a regular speaker at meetings of the Independent Labour Party and the Labour Church, both of which had a strong presence in the industrial North. Many meetings were held in the open air and attracted large crowds, such as in Farnworth on Sunday July 28th 1905. He spoke in Bolton’s Temperance Hall on several occasions during 1905, to huge audiences.

Revolution in the Colne Valley

In the Spring of 1907 the sitting Liberal MP for Colne Valley, near Huddersfield, resigned his seat following his elevation to the House of Lords. A by-election was set for July 18th, with the Liberals expecting an easy win. How wrong they were. The socialists got to work with enthusiasm and Grayson – a young man of 26 – was invited to apply to be the ‘Labour and Socialist’ candidate, narrowly beating a local man.

He had huge charisma – a handsome and flamboyant figure who could captivate his audience.  Even in small mill villages like Golcar, Honley and Delph Grayson was able to attract audiences in the hundreds and sometimes even more. Grayson’s eve of poll message ‘to the electors of the Colne Valley’ pulled no punches:

Even in small mill villages like Golcar, Honley and Delph Grayson was able to attract audiences in the hundreds and sometimes even more. Grayson’s eve of poll message ‘to the electors of the Colne Valley’ pulled no punches:

“I am appealing to you as one of your own class. I want emancipation from the wage-slavery of Capitalism. I do not believe that we are divinely destined to be drudges. Through the centuries we have been the serfs of an arrogant aristocracy….the time for our emancipation has come. We must break the rule of the rich and take our destinies into our hands..the other classes have had their day. It is our turn now!”

Many of the looms in the weaving sheds of the valley had red ribbons tied to them, showing the weavers – mostly women – where they stood. Local children wore red rosettes and sang socialist songs when Grayson spoke.

The election result was announced on July 19th and it astonished the country. Grayson received 3,648 votes beating the Liberal with a majority of 153. The Conservative came a close third. When the vote was announced at Slaithwaite Town Hall, in the words of a local journalist, “pandemonium prevailed…the wild scene of enthusiasm which followed the announcement of the figures is indescribable.”

The result shook the political establishment to its foundations, with many fearing – or hoping – that a socialist revolution was imminent. Yet it wasn’t to be and Grayson’s parliamentary performance was erratic. He preferred touring the country speaking at socialist meetings than the dreary work of being a back-bench MP, though on one notable occasion he was expelled from the House of Commons for disrupting proceedings in support of the unemployed – an action that won him warm support amongst grassroots socialists but further alienated him from mainstream Labour MPs who were besotted with parliamentary procedure. He continued to visit Bolton and in February 1909 was the guest of honour at Bolton Socialist Party’s ‘Merrie England Bazaar’.

A darker side

There was a darker side to his behaviour. Possibly through the stress of his campaigning, he developed a strong taste for whisky and reached the point where he was consuming a full bottle every day. He enjoyed the social life of the London clubs and was always something of a hedonist, enjoying ‘the good life’. He was hugely attractive to women but also had several affairs with men, which seem to go back to his early 20s. Homosexuality was still a crime and Grayson had to tread carefully to avoid being exposed.

Grayson remained an MP for just three years. He lost the seat in 1910 but continued his socialist campaigning activities. On October 23rd he was speaking to a packed meeting in Bolton’s Temperance Hotel, no doubt amused by the irony of the location. By then, he was making a tenuous living from his speaking engagements though finding it difficult to maintain his lavish lifestyle and increasingly heavy drinking.

Marriage to Ruth

In November 1912 he married Ruth Nightingale, an actress whose stage name was ‘Ruth Norreys’. She was the daughter of an affluent Bolton family. Her father, John Webster Nightingale, was a banker and he shared a substantial house in Smithills with his wife Georgina and housekeeper/maid Jane Mackereth. Victor and Ruth had a daughter, Elaine, in 1914. The relationship with the Nightingales was to become increasingly important for Grayson over the next eight years.

By 1914 his health had deteriorated and he found himself in the Bankruptcy Court. Friends and supporters, helped by his father in law, assisted. Everything changed when war broke out in November of that year.

Most left-wing socialists were bitterly opposed to the war. Grayson took a very different stance, not only publicly supporting the Allies but advocating conscription and demonising the German people as a war-mongering race. Grayson spent some time in Australia speaking on pro-war platforms, then returned to Britain and continued to support the war effort, possibly with some financial help from the Lloyd George government. In 1917, he and his wife Ruth went to New Zealand where she had some theatrical engagements. Whilst there, he was involved in socialist activity but continued to support the war effort, joining the New Zealand armed forces (ANZAC) in 1917. He took part in some of the heaviest fighting of the war and was wounded at the Battle of Passchendaele, one of the bloodiest encounters in the whole conflict.

He returned to England in 1918 and was devastated by the death of his wife in childbirth, in February of that year. The baby was stillborn. Grayson agreed with the Nightingales for them to look after the four-years’ old Elaine, who lived at the family home. By then, the family had moved to ‘Ellerslie’, a large house in The Haulgh. Grayson, living in London, was a regular visitor to Bolton, each weekend, with his own room and even pet dog which he named ‘Nunquam’, the pen name of Robert Blatchford. He kept a hidden supply of whisky under the floorboards of his room. His visits were ostensibly to see his young daughter. I wonder if there were other motives?

Post-war uncertainties

Grayson had little involvement in post-war politics. His estrangement from the Labour Party was virtually complete. Harry Taylor quotes a letter from parliamentary journalist Sidney Campion suggesting that Grayson “was a disillusioned socialist turned Tory” and his father-in-law approached Tory leader Bonar Law to employ him as a propagandist. The source of this came from Charles Sixsmith, who was part of Bolton’s ‘Walt Whitman’ circle which included another Nightingale – Fred, who lived, on Chorley Old Road. Whether Fred and John were related isn’t clear but they may have been closer in their politics than historians have given them credit for. John W. Nightingale was a friend of Sixsmith’s, who was a prosperous capitalist, with mills in Farnworth. He was a socialist and also, like Grayson, bi-sexual. Did Grayson and Sixsmith know each other? John W. Nightingale, certainly in later years, was a member of the Swedenborgian church which had much in common with the mystical beliefs of the Whitmanites.

Disappearance

The strangest part of the ‘Grayson Story’ comes next. In September 1920 he left his apartment in London accompanied by two men, telling his landlady that he would be away for some time. In fact, he was never seen again, at least definitively. Some accounts suggest he was murdered, others that he left the country to start a new life. At the time, there was a ‘cash for honours’ scandal brewing which Grayson may have threatened to expose and there are suggestions that he was ‘removed’ by a shadowy character called Maundy Gregory, who had links to the intelligence services.

His daughter Elaine was devastated by his disappearance, being told by Jane, the family maid, that her father “will never come again because he’s going to travel…but he’ll never forget you…and one day perhaps he may come back.”

There are several accounts of him being seen, in places as varied as Melbourne, Madrid and on the London tube. However, there seems to be strong evidence that he was living in Maidstone, Kent, in the 1930s.

He was not in communication with his parents in Liverpool or his Bolton in-laws. However, Elaine’s grandmother Georgina seems to have been convinced that Grayson might return to Bolton and ‘kidnap’ the young girl. She lived a cosseted life being driven to and from school in the family car – a rare luxury at the time – and only being permitted a very limited social life.

During the Second World War there was a government-sponsored investigation into Grayson’s disappearance, led by the well-respected Chief Inspector Arthur Askew, of Scotland Yard. The report was never published but subsequently, after his retirement, Askew sent a short note to his biographer Reg Groves saying “Grayson married – settled in Kent”.

There seems to be a possibility that Grayson died in an air raid in 1941. Certainly, his mother-in-law’s almost hysterical fear of Grayson’s re-appearance had diminished by the early 1940s. Georgina herself died in 1942.

Parentage questions

There is one final twist to the story, relating to Victor’s parentage. There had long been suggestions that his parents in Liverpool were not his biological parents. As Georgina lay on her death bed, accompanied by maidservant Jane and her grand-daughter Elaine, she kept muttering the name ‘The Marlboroughs’. Elaine was puzzled by this, but after Georgina’s death, Jane said to her “Elaine, don’t you realise your grandmother was telling you who your father really was?”

Amongst Grayson historians this story is treated with different emphasis. Harry Taylor rejects the possibility that Grayson was the illegitimate child of the powerful Marlborough family, whose members included Winston Churchill – with whom Grayson enjoyed a friendly relationship whilst in the Commons, and after. David Clark is not so sure and offers evidence that the story might be true.

There are so many ‘known unknowns’ in the Grayson story, above all what happened to him after 1920 and the riddle of his parentage. As Jeremy Corbyn writes in his foreword to Harry Taylor’s book, says “the ever-secretive British state knows the answer, somewhere in Scotland Yard or the Home Office, the truth is known.” He’s right, and I think there is more to be discovered about his Bolton links, including the role of his father-in-law John W. Nightingale and the maid who seemed to know much, Jane Mackereth.

I am indebted to Lord David Clark, Harry Taylor, Sheila Davidson and Julia Lamara (Bolton History Centre) for their assistance. Harry Taylor’s book Victor Grayson: in search of Britain’s lost revolutionary, is published by Pluto (2021), David Clark’s Victor Grayson – the man and the mystery is published by Quartet (2016).

Use your local shop

As well as being able to order directly, my books are available in a number of shops across the North-West and beyond. At the moment they are:

- Justicia Fair Trade Shop, Knowsley Street, Bolton

- Ebb and Flo, 12 Gillibrand Street, Chorley

- The Wright Reads, Winter Hey Lane, Horwich

- Bunbury’s Real Ale Shop, 397 Chorley Old Road

- Pendle Heritage Centre, Barrowford

- Smethurst’s Newsagents, Markland Hill

- Pike Snack Shack, Rivington

- Horwich Heritage Centre

- A Small Good Thing, Church Road Bolton

- Books and Bygones, Chorley

- Carnforth Bookshop

- The Lakeland Gallery, Bo’ness

- Penrallt Bookshop, Machynlleth

- Beach Hut Gallery, Kents Bank

HS2: the wrong mindset

The response to the Government’s ‘Integrated Rail Plan’ (IRP) has been almost universally hostile. The chopping of the ’eastern leg’ from Birmingham to Leeds and ‘scaling back’ of the east-west line (Northern Powerhouse Rail’) has invoked particular ire, with cries of ‘betrayal of the North’ coming from an unlikely coalition of so-called ‘red wall’ Tories and Labour.

But..there were good arguments for a fundamental review of HS2, particularly in the light of Covid, which many people in transport think will lead to long-term changes in people’s travel behaviour – in particular, less business travel and commuting and more leisure journeys (less time sensitive).

HS2 as originally conceived – a very high-speed route (speeds of up to 225 m/ph or 360 km/h) from London to Birmingham, Leeds and Manchester, represents a particular approach to transport and wider spatial planning, which prioritises the major cities, at the expense (unless there is a complementary plan in place) of smaller towns and cities. In his Foreword to the IRP Boris Johnson recognises the adverse effect that HS2 to Leeds would have had on other places currently served by fast and frequent trains: “Under those plans, many places on the existing main lines, such as Doncaster, Huddersfield, Wakefield and Leicester would have seen little improvement, or a worsening, in their services..” The same applies to the ‘western leg’ to Manchester, which is still going ahead: so – tough on Stockport, Stoke-on-Trent, Macclesfield, Stafford and Rugby.

The thinking behind HS2 reflects a particular approach to transport which I would argue is 20 years out of date. It is a move away from the earlier car-led approach of the 1960s which saw motorway building, rail closures, and towns and cities carved up for the motor car. The ‘Very High-Speed Rail’ approach prioritises the needs of major cities and ‘out of town’ development with huge parkway developments, in the case of HS2 at Birmingham Interchange. The proposed ‘dead-end’ stations at Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds would have been poorly connected with the rest of the rail network but developers would (or still will) have a field day with opportunities for major development schemes around the three termini. And anyone who knows much about railways will recognise that terminal stations are bad news, soaking up capacity, limiting the full opportunities of fast, long-distance trains.

The ‘very high-speed’ thinking behind HS2 means that you can’t bother with serving even quite large towns and cities along the route as it slows everything down creating longer end to end journeys which ‘the model’ hates. And of course the other big down side of ‘very high speed rail’ is that the need for such high speeds means you have to build a railway that is very straight – either a lot of tunnelling which is costly and very destructive on the environment, or ploughing through established communities and sensitive landscapes. Running long trains at 225 m/ph sucks up a lot of energy.

There is a further argument against HS2 which is more difficult to prove but has certainly been raised in some academic papers. High-speed rail, or any transport corridor, is a two-way street. The pro-HS2 hype is full of talk about how HS2 will ‘level-up’ the North. Equally, it could do more to benefit London and the south-east. Why should firms bother to maintain a major regional office in Manchester or Birmingham when you can be in London in next to no time? A far more likely economic generator would be better inter and intra-regional rail links across the North and Midlands, which happens to be what most people say in opinion polls, when asked.

This approach of ‘very high speed rail’ can work if you’re a country the size of France, China or the United States. The German approach is more nuanced with significant stretches of high-speed rail but part of a well integrated network of inter-regional and local services. It is less suitable to a smaller country such as Britain, with densely populated areas. One of the most trumpeted-arguments in support of HS2 has been the idea that it ‘frees up capacity’ permitting freight and regional passenger services. That’s only true up to a point and the main capacity benefits of HS2 will be south of Rugby. Where it frees up capacity in the North it is at the expense of existing InterCity services being re-routed via HS2 meaning that major centres like Stockport and Stoke will lose out. If we’re told that the existing InterCity services (3 an hour Manchester – London, pre-Pandemic) will continue, you wonder a) what the point of HS2 is in the first place, and crucially b) where all the extra passengers wanting to get to and from London in 71 minutes will come from.

A third approach would be a more integrated rail-based strategy with a core InterCity network which would aim for speeds of up to 160 m/ph and link major centres across the country, with good connections to regional, local rail and light rail services. This would be a bit more like the German approach, taking greater account of the needs of large towns and cities between the main centres, with good connectivity to all parts of the rail network. Such an approach would be a hybrid of new and existing, upgraded, lines and it would go through to Carlisle, Newcastle, Glasgow and Edinburgh.

It could be argued that the newly-published IRP does that, though I’d say it’s more of a ‘politics-led’ plan than anything that is strategic. It tried (and failed) to satisfy politicians in the North with a mix of new and upgraded lines and electrification schemes, notably the Midland Mail Line taking electric trains beyond the south Midlands to Derby and Nottingham, Chesterfield, Sheffield and Leeds.

Bradford is the big loser in the IRP, so as a concession the short section of line from Leeds to Bradford via New Pudsey will be electrified, shaving a few minutes of journey times. Quite what the trains do when they get to Bradford isn’t said, presumably they’ll speed back to Leeds. Yet all trains from Leeds to Bradford go beyond the city, to Halifax, Hebden Bridge, Rochdale and Manchester or across to Burnley, Blackburn and Preston. Any sensible strategy would have seen those lines fully electrified as part of the Bradford scheme. Even better would be a ‘Bradford CrossRail’ for existing regional and additional InterCity services, joining up the two separate routes into the city and permitting a ‘scissors’ shape network north-west of Leeds which would permit new journey options and improved capacity into and out of Bradford.

The ‘core’ of HS2’s western leg, to Manchester, will be a major engineering challenge and aims to link up with ‘Northern Powerhouse Rail’ and serve Manchester Airport. The route to Scotland and further north is likely to be re-considered with the proposed new ‘Golborne Loop’ scrapped. A sensible strategy for the ‘West Coast Main Line’ north of Crewe would see maximum use of the existing route with more capacity, track realignment to get faster speeds and some new sections, north and south of the border, to improve overall journey times but still serve main centres such as Warrington (with interchange with Northern Powerhouse Rail as per IRP), Wigan, Preston, Lancaster, Oxenholme (for the southern Lakes) Penrith and Carlisle.

I remain unconvinced that a terminal station at Manchester Piccadilly is the right solution. Termini are operationally difficult and soak up capacity. A through station that would help solve the ‘Castlefield Corridor’ dilemma, perhaps underground, would have been a better solution.

Perhaps the biggest criticism is the length of time the proposals will actually take – with completion of the Manchester parts of the scheme being well into the 2040s. So I won’t be around to see them!

The Rail Reform Group has produced a good statement on HS2 (sub-titled ‘A considered response’ which is available on www.railreformgroup.org.uk

Lancashire Loominary Publications

Allen Clarke/Teddy Ashton – Lancashire’s Romantic Radical

This is my latest book and tells the story of Lancashire’s errant genius – cyclist, philosopher, unsuccessful politician, amazingly popular dialect writer. The book outlines the life and writings of one of Lancashire’s  most prolific – and interesting – writers. Allen Clarke (1863-1935) was the son of mill workers and began work in the mill himself at the age of 11. It is a completely new edition of the 2009 edition, and includes an entirely new chapter on his railway writings which include Horwich Loco Works, ‘The Club Train’ and the adventures of Ginger the Donkey.

most prolific – and interesting – writers. Allen Clarke (1863-1935) was the son of mill workers and began work in the mill himself at the age of 11. It is a completely new edition of the 2009 edition, and includes an entirely new chapter on his railway writings which include Horwich Loco Works, ‘The Club Train’ and the adventures of Ginger the Donkey.

Moorlands, Memories and Reflections

2020 was the centenary of the publication of Allen Clarke’s Moorlands and Memories, sub-titled ‘rambles and rides in the fair places of Steam-Engine Land’. It’s a lovely book, very readable and entertaining, even if he sometimes got his historical facts slightly wrong. It was set in the area which is now described as ‘The West Pennine Moors’ It also included some fascinating accounts of life in Bolton itself in the years between 1870 and the First World War, with accounts of the great engineers’ strike of 1887, the growth of the co-operative movement and the many characters whom Clarke knew as a boy or young man.

My book is a centenary tribute to Clarke’s classic – Moorlands, Memories and Reflections. It isn’t a ‘then and now’ sort of thing though I do make some historical comparisons, and speculate what Clarke would have thought of certain aspects of his beloved Lancashire today.

With Walt Whitman in Bolton – Lancashire’s Links to Walt Whitman.

This charts the remarkable story of Bolton’s long-lasting links to America’s great poet. Bolton’s links with the great American poet Walt Whitman make up one of the most fascinating footnotes in literary history. From the 1880s a small group of Boltonians began a correspondence with Whitman and two (John Johnston and J W Wallace) visited the poet in America. Each year on Whitman’s birthday (May 31) the Bolton group threw a party to celebrate his memory, with poems, lectures and passing round a loving cup of spiced claret. Each wore a sprig of lilac in Whitman’s memory.

The group was close to the founders of the ILP – Keir Hardie, Bruce and Katharine Bruce Glasier and Robert Blatchford. The links with Whitman lovers in the USA continue to this day.

The Works: a tale of love, lust, labour and locomotives

I’ve had a steady flow of orders for The Works, my novel set mostly in Horwich Loco Works in the 1970s and 1980s, but bringing the tale up to date and beyond – a fictional story of a workers’ occupation, Labour politics, a ‘people’s franchise’ and Chinese investment in UK rail. I’ve had lots of good reactions to it, with some people reading it in one session. The Morning Star hated it. It has been particularly popular in Horwich, which you would kind of expect, but it was nice to see people who have spent a lifetime in the loco works telling me how much they enjoyed it.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

ACTUALLY EXISTING CUSTOMERS’ ORDER FORM

Christmas 2021 (offers end December 31st 2021 but check)

Name……………………………………………………………………………………..

Delivery Address…………………………………………………………………….

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Post code…………………….

Phone……………………………………………..

email………………………………………………

| Quantity | Title | Price ( + delivery) |

| Lancashire’s Romantic Radical | 15.00 + £3 | |

| With Walt Whitman in Bolton | 6.00 + £3 | |

| Moorlands, Memories and Reflections | 15.00 + £3 | |

| The Works | 6.00 + £3 | |

| Total |

See above re bundles – please note:

- If you buy any two, the lowest priced book is free

- You can buy all four for £30 plus postage if required

- Maximum postage on all orders is £4 within the UK. Enquire for overseas rates

- Local delivery (free) is by Bolton Bicycling Bookshop, otherwise Royal Mail

Please send cheque for total amount made to ‘Paul Salveson’to 109 Harpers Lane, Bolton BL1 6HU.

PLEASE TELL ME IF YOU WOULD LIKE THE BOOKS SIGNING AND /OR DEDICATING

If paying by BACS the account details are:

Dr P S Salveson (it’s a personal account) sort code 53-61-07

A/C no. 23448954.

Please email me with your order details and put your name and book e.g. ‘MMR’ or ‘Works’ as the reference when paying.

Lancashire Loominary 109 Harpers Lane BOLTON BL1 6HU

Phone: 07795 008691

2 replies on “Lancashire Loominary December issue”

Hi Paul can you give me details of your book on Blackpool and my grandfather as if it is mill orientated perhaps you could use the mill to promote your book my number is 07564161977

Thanks for your continued interest in Allen. xx Hope you and your family are in good health,

Hi Shirley, apologies for late resonse! I’m still hoping to do a live talk on Allen Clarke and Blackpool/The Fylde but becoming more difficult with covid resurgence. I may do a talk on zoom duing January as a ‘warm up’ for something later, and the Mill would be an ideal place. All good wishes for the season Paul xx